Home School Researcher Volume 39, No. 4, 2025, p. 1-9

Hannah Hobson

Elementary Music Teacher, Lancaster Elementary School, Norwell Community Schools, Bluffton, Indiana, hannah.hobson@nwcs.k12.in.us

William Sauerland

Associate Professor of Music, School of Music, Purdue University Fort Wayne, Fort Wayne, Indiana, sauerlaw@pfw.edu

Abstract

In recent years, the number of families choosing to homeschool in the United States has grown. The Indiana State Department of Education exempts homeschools from the curriculum mandated for public schools, enabling homeschools the freedom to educate students in the way they choose. This curricular autonomy can lead to disproportionate access to music education for homeschool students. The purpose of this study is to investigate music education in homeschools and to understand the perceived value of music education to homeschool educators. A survey instrument was sent to homeschool educators through a homeschool organization, which generated 44 responses representing 121 students. The survey concerned the music-related activities and delivery of music instruction provided to students in their homeschool education. Respondents were also invited to share their perspectives on the importance of music in their students’ education. Using the 1994 National Standards for Music Education as a concise framework for music-related activities, the researchers assessed the different forms of musical experiences provided to homeschool students. Over 80% of respondents indicated singing is the most frequent form of music making, while music composition is the least frequent form of music making in this population. A majority of homeschool educators indicated that music education is either very or extremely important in their homeschool curricula. Together with additional findings from the study, the researchers concluded that homeschools might need greater access to music education resources to provide students with a broader array of music making experiences.

Keywords: Homeschooling, home schooling, home education, music, music education, musical experiences, music opportunities

Homeschooling is the practice of educating a student in grades K-12 not enrolled as a full-time student in a traditional public or private school. In the United States, educational reforms advocated by John Holt and Raymond Moore during the 1960s and 1970s played a pivotal role in legitimizing homeschooling, driven by a confluence of social, cultural, religious, political, and economic factors (Davis, 2013; Gaither, 2008; Murphy, 2013). The number of students in homeschool education has increased in the last several decades (Newberry, 2022; Ray, 2022), and in 2023, The Washington Post reported homeschooling is “America’s fastest-growing form of education” (Jamison et al., 2023). A study by Brian Ray, a leading researcher in homeschool education, estimated that, in the 2021-2022 academic year, there were 3.135 million children grades K-12 being homeschooled, accounting for slightly over 5% of all students receiving a K-12 education in the United States (Ray, 2022).

In the state of Indiana, the site of this research study, homeschools are defined as non-public, non-accredited schools and must follow these four guidelines:

(1) Students must receive education from the age of 7-18 with a minimum of 180 days of instruction each year (I.C. 20-33-2-6; I.C. 20-33-2-8);

(2) Student attendance records must be kept and produced if requested by the state or local school district (I.C. 20-33-2-20);

(3) The instruction given must be in English and equivalent to that which is given in public schools (I.C. 20-33-2-4; I.C. 20-33-2-28);

(4) Homeschool students are exempt from the curriculum mandated for public schools (I.C. 20-33-2-12).

These state regulations afford homeschool educators with greater autonomy in curricular decision-making than their counterparts in public schools. In Indiana public elementary and middle schools, the core curriculum includes classes in English, mathematics, physical and life sciences, social sciences and history, physical education, and visual and performing arts. Indiana public high schools must offer a similar curricular framework; however, classes in art and music are encouraged but not compulsory.

Arts education advocates have asserted for the inclusion of music education in school core curriculum, citing that musical learning enhances brain development, fine and gross motor skills, and social intelligence, among other benefits (Blakeslee, 1994; Campbell & Scott-Kassner, 1995; Levitin, 2007). Multiple studies have found that participation in music classes is positively correlated with enhanced academic achievement, including higher standardized test scores, improved executive functioning, and stronger verbal and visual memory (Guhn et al., 2020; Hille & Schupp, 2015; Jaschke et al., 2018; Kinney, 2008). Additionally, research suggests that active engagement in musical training—such as through music classes and instrumental lessons—yields greater cognitive and academic benefits for students than passive music listening (Hyde et al., 2009).

Music teaching in U.S. public schools is steered by government legislation, teacher education, and professional music organizations, such as the National Association for Music Education (NAfME). For over thirty years, NAfME has guided school music curricula through the National Standards of Music Education. The original standards of 1994 were developed to engage learners in a diverse range of musical activities, such as singing, playing musical instruments, listening to and describing music, and connecting music to history and other arts (Blakeslee, 1994). In 2014, NAfME revised its standards to place less emphasis on specific musical activities and instead emphasize four core processes: creating, performing, responding, and connecting across a broad spectrum of musical experiences. Indiana Department of Education’s standards for music education align with the NAfME standards to promote a comprehensive and diversified music curriculum.

Despite a growing number of students within homeschool education, there is limited scholarship on the music education in homeschools. Indiana homeschool guidelines provide curricular autonomy which can lead to disproportionate access to music education for homeschool students. The purpose of this study is to investigate music education in homeschools and to understand the perceived value of music education to homeschool educators.

Literature Review

In research related to homeschool music education, scholars have employed a variety of methodological approaches. Survey studies conducted by Young (1999), Myers (2010), Hamlin (2019), and Murphy (2021) have contributed to a broad understanding of the field, while case studies by Silverman (2011), Parker (2012), and Anders (2023) have offered more focused, in-depth insights into specific contexts and experiences. Nichols (2005, 2012) used phenomenological inquiry and narrative inquiry in two different studies, providing an insider’s view of homeschool music education. These nine studies have provided a foundation for the current study and validated the importance of investigating music education in homeschools.

In a commentary-based article predating the aforementioned research studies, Fehrenbach (1995), a music teacher, proposed a music curriculum that emphasizes listening to music, composing, and performing. Fehrenbach (1995) suggested that in addition to these music activities, “there is also ample opportunity to integrate music into other subjects, since the various curriculums are all under the auspices of the parents” (para. 4). Fehrenbach (1995) promoted a learner-centric notion of homeschooling, suggesting that homeschool educators assess students’ ability and interest in music when making decisions regarding music education curriculum.

Young (1999) researched the nature of homeschool music education in Broome County, New York. In a survey study with 147 respondents, homeschool music education primarily comprised of listening to music, singing, and learning to play an instrument. Furthermore, homeschool teachers relied on outside music instructors and organizations to provide individual and group music lessons. While Young (1999) indicated that homeschool music education might provide greater access to individual lessons than public schools can offer, he also averred, “Music education of [homeschooled] students may not be as comprehensive as the music education provided in public schools” (Young, 1999, p. 122). Young suggested national music education organizations, such as the National Association for Music Education, develop more resources for homeschools.

In a 2010 survey study with 43 respondents, Myers examined the music education of homeschools in a Midwestern metropolis. Seeking to understand if homeschool music teaching aligns with the 1994 National Standards for Music Education from the National Association for Music Education, Myers (2010) found that homeschool learners most frequently study keyboard, voice, and string instruments through individual instruction outside of the homeschool or through family activities. Myers (2010) asserted that this form of musical instruction facilitates homeschool students’ proficiency of reading and performing music. Additionally, Myers (2010) noted that other activities listed in the music education standards, such as composing and improvisation, were found least likely taught in homeschools.

In discussing homeschoolers’ acquisition of cultural capital—the knowledge, skills, and cultural competencies that contribute to social mobility—Hamlin (2019) asserted, “In homeschooling contexts, varied expertise needed to teach music, art, literature, and foreign language may present homeschool teachers with considerable challenges” (p. 315). Hamlin’s (2019) study indicated that approximately 40% of homeschools “taught two (or fewer) of these subjects [music, art, literature, and foreign language] during the years that they homeschooled” (p. 324). Hamlin (2019) further suggested that expensive resources and equipment for these subjects, such as musical instruments or the cost of outside music instruction, creates financial barriers to the inclusion of music education within homeschools.

Murphy’s 2021 survey study explored homeschool music education and found that homeschool educators sourced music curricula from libraries, websites, and other technology, in addition to individual instrument instruction and church music participation. Although Murphy (2021) discovered that homeschool teachers value creating, listening, and responding to music, fewer opportunities for music making were available to homeschool students compared to non-homeschool students. Murphy (2021) noted that homeschool educators employed both informal music instruction, such as YouTube videos, and formal instruction, including music lessons and published curricula. This research suggested that homeschool students received a “piecemeal” (Murphy, 2021, p. 140) music education, rather than a cohesive, comprehensive curriculum.

Employing case study methodology, Silverman (2011), Parker (2012), and Anders (2023) offered further incite to homeschool music education. Silverman (2011) examined the nature, values, and pedagogical strategies of the New Jersey Homeschool Association Chorale. The revealed that choral teaching in this setting emphasized “care, community, cultural pluralism, and spirituality” (Silverman, 2011, p. 185). Parker (2012) investigated homeschool music education by studying the pre-college musical experiences of two music education majors, both homeschooled before college. These homeschooled students benefited from individualized music instruction and were well-prepared for post-secondary pursuits in music education. However, Parker (2012) also observed that the absence of a traditional public or private school classroom teacher as a role model may hinder the development of teacher identity among some homeschool students—an element often considered valuable for pre-service and early-career music educators. Anders (2023) investigated homeschool music curriculum in Arkansas and discovered that homeschool educators desired to provide a “comprehensive music education curriculum” (p. viii), but felt unable to do so due to a lack of music education resources for homeschools.

Nichols conducted research studies on homeschool music education in 2005 and 2012. In the first study, Nichols (2005) examined the music education of three homeschools, finding, “Instruction may be child centered and the students may have some voice in the decision-making process, but the fundamental philosophy and curricular selection is ultimately decided by the parents” (p. 38). Corroborating Young’s (1999) study, Nichols (2005) found that listening to music, singing, and playing instruments were common music-related activities of homeschool students. Nichols (2005) reported that church music activities, including worship band and handbell choir, were foundational in the music education of select homeschool students. Additionally, Nichols uncovered that some homeschools practiced a “hobbyist approach” (2005, p. 38) while others were more deliberate in their music education curricula.

Through narrative inquiry, Nichols’s 2012 study explored the music education of Jamie, a homeschool student, who participated in multiple instrumental ensembles in Arizona. State regulations allowed Jamie to participate in public school music classes, including choir, marching band, concert band, and orchestra. Jamie also took classes in music theory and music history while finishing high school. Jamie’s narrative demonstrated that curricular autonomy in her homeschool setting provided her with the opportunity to take multiple music classes prior to college—an opportunity not available to her public school peers.

A review of the literature indicated music-related activities and instructional approaches vary from homeschool to homeschool. While individual music lessons seemed the most prevalent form of instruction, some students participated in music ensembles through local schools, community organizations, and churches. Other students engaged in music learning through listening activities and reading supplementary materials found on websites and other technologies. Despite the aforementioned studies, research on music education within homeschools remains limited. Most of the existing studies have been conducted with small sample sizes, highlighting the need for further replication to enhance the understanding of homeschool music education.

Background and Purpose

This research originated as an undergraduate project with Hobson (she/her), who developed the study based on her personal experience as a homeschooled student from kindergarten through grade 12. As a homeschool learner, Hobson was actively involved in individual piano, violin, and voice lessons, along with participation in a community children’s choir and youth orchestra. She received a Bachelor of Music Education degree before starting work as an elementary music teacher. As Hobson’s research advisor, Sauerland (he/they) had little experience and knowledge of homeschool education prior to this project. Hobsons’s insider knowledge, along with Sauerland’s novice point-of-view, provided valuable insider-outsider perspectives on the background of the study and the analysis of the research data.

This study is underpinned by Hobson’s experience with homeschooling, a review of the relevant literature, and an analysis of the legal framework governing homeschooling in the state of Indiana. The Indiana State Department of Education exempts homeschools from using the curriculum mandated for Indiana public schools (Ind. Code, 2020), and thus, a wide variety of approaches to music education may result. Therefore, an evaluation of the music-related activities and instructional approaches that constitute homeschool music education is needed to better understand the musical training and experiences of homeschool students.

The purpose for this study was to understand the music education curricula and music experiences of homeschool students. Additionally, the study aimed to examine homeschool educators’ perspectives on value of music education within their broader curricular decisions. To this end, two research questions guided the study:

1. What music-related activities and instructional approaches are provided to homeschool students?

2. What are the perspectives of homeschool educators concerning music education in students’ overall curriculum?

Methodology

Data were collected using a survey instrument developed in Qualtrics, a web-based platform for survey distribution and data analysis. Prior to dissemination of the survey, two colleagues (a music education university faculty member and a retired homeschool educator) reviewed the online survey to improve readability and internal validity (Wiersma & Jurs, 2009). Upon university IRB approval, the survey instrument was distributed to homeschool educators through a weekly e-newsletter of Fort Wayne Area Home Schools (FWAHS), an organization supporting approximately 325 distinct homeschools. Survey study recruitment through FWAHS employed voluntary sampling, which may have introduced self-selection bias, as homeschool educators with strong views—either supportive or critical of music education—were potentially more inclined to participate. Criteria for participation included (1) membership in FWAHS, and (2) self-identification as a homeschool teacher. Consent for participation in the study was obtained through the first question on the survey. Here, an overview of the study, potential risks and benefits, and a statement of confidentiality were provided. If participants declined consent, the survey instrument automatically restricted access to the remaining questions, preventing them from viewing or completing the survey.

The survey instrument contained 16 questions, divided into four sections: (1) study overview and consent, (2) demographic information, (3) music-related activities and instructional delivery, and (4) homeschool teacher perspectives. Respondents provided demographic information concerning the number of students they homeschooled and the grade level of these students: Elementary School (K-5), Middle School (6-8), and High School (9-12). Next, participants responded to a multiple-choice question regarding the types of music-related activities their students regularly participated in, drawn from the 1994 National Standards for Music Education of the National Association for Music Education (Blakeslee, 1994). Participants were offered the following options for music-related activities and could select as many as relevant to their homeschool curricula:

1. Singing, alone and/or with others;

2. Performing on instruments, alone and/or with others;

3. Improvising melodies (note: improvising refers to the act of creating melodies in real time, with no intention of notation or future reproduction);

4. Composing music (note: composing refers to the act of creating music, often over time, with notation, formal or informal, for the purpose of later reproduction.);

5. Reading and notating music;

6. Listening to, analyzing, and describing music;

7. Evaluating music and music performances; and

8. Connecting music to other disciplines (i.e., art, history, science).

The survey instrument contained short definitions for “improvising” and “composing” to heighten reliability in responses. For survey ease, the researchers combined standards eight and nine of the originally published 1994 music education standards (Standard 8: “Understanding relationships between music, the other arts, and disciplines outside the arts;” Standard 9: “Understanding music in relation to history and culture.”)

The researchers wanted to understand student engagement in music through different instructional approaches (i.e., group classes, individual lessons, ensemble participation), if any, being used to teach music-related activities. Drawing on relevant literature and widely recognized instructional approaches, the researchers created a list of options that were not derived from the 1994 National Standards for Music Education. The survey allowed the participants to select all choices that were applicable to their homeschool:

● Individual Piano Lessons;

● Individual Voice Lessons;

● Individual Instrument Lessons (not piano);

● Music Appreciation Lessons/Courses;

● Choir;

● Band;

● Orchestra;

● Dance/Movement;

● Musical Theatre;

● Other (fill in the blank)

If participants indicated Other, they were prompted to provide additional explanation in a follow-up question. Dance/Movement and Musical Theatre were both included as response options, as both disciplines reinforce and apply skills and concepts learned through music education.

In addition to examining the music-related activities and instructional approaches used in homeschools, the researchers sought to understand homeschool educators’ perspectives on the value of music education in their students’ overall curriculum. Three questions were included on the survey regarding their perspectives. Participants rated their opinion on the presence of music education in their students’ overall curricula at the elementary, middle, and high school levels. For all three educational levels, the surveyed used a Likert-type scale to indicate importance from extremely important to not at all important. Through open-ended questions, the educators were then given the opportunity to elaborate on what value, if any, they believe music education plays in their students’ education. Participants were asked if they believed the value of music education in homeschool curriculum changes depending on the grade level of their students and why or why not. Finally, participants were invited to share additional open-ended feedback or insights related to this study. Although concerned with the broadness of this question, the researchers thought it was important to give the educators a place to provide their thoughts and opinions they felt relevant to the study.

Findings

A total of 44 homeschool educators (n = 44) responded to the survey, resulting in a 14% response rate. These responses represented 121 students, with an average of approximately 2.75 students per homeschool. There were 11 homeschools with one student each, and one homeschool with nine students – the largest grouping in our data. Elementary-age students (grades K-5) represented 44.59% of our population, with 29.73% students from middle school (grades 6-8), and high school (grades 9-12) with 25.68%.

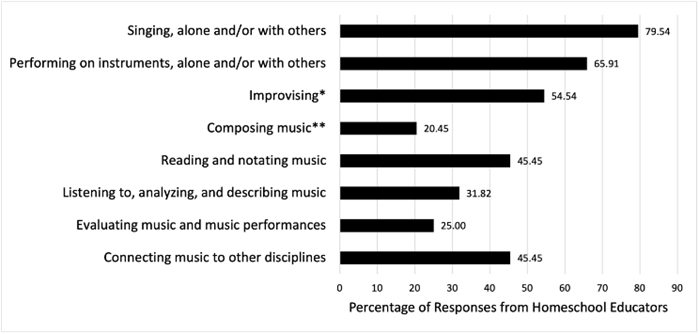

In alignment with the stated objective of examining music-related activities and instructional methods in homeschooling, the survey was developed based on the 1994 National Standards for Music Education (Blakeslee, 1994). Student engagement in specific music-related activities is shown in Figure 1. The data indicated that a majority of participants (79.54%, n = 35) identified Singing, alone and/or with others, as a form of musical engagement. Additionally, 65.91% (n = 29) of students were reported as Performing on instruments, alone and/or with others. Nearly thirty-two percent (n = 14) of homeschool educators selected Listening to, analyzing, and describing music as a music-related activity for their students, while Evaluating music and music performances (25%, n = 11) and Composing music (20.45%, n = 9) ranked as the two least common activities.

Figure 1

Music Related Activities

Note. N = 44.

*Improvising refers to the act of creating melodies in real time, without intention of notation or future reproduction. **Composing refers to the act of creating music, often over time, with notation, formal or informal, for the purpose of later reproduction.

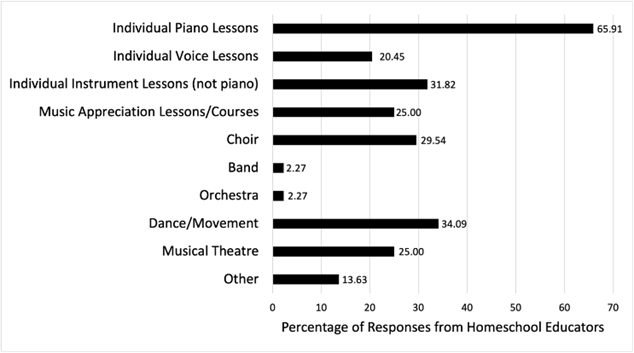

The researchers also aimed to examine the delivery of music instruction in homeschooling, such as individual music lesson instruction and participation in music ensembles (i.e., choir, band, orchestra). Figure 2 shows that Individual Piano Lessons (65.91%, n = 29) were most prevalent, alongside Dance/Movement (34.09%, n = 15) and Individual Instrument Lessons (not piano) (31.82%, n = 14). Participation in group instrumental ensembles, Band (2.27%, n = 1), and Orchestra (2.27%, n = 1), were the least popular. Other (13.63%, n = 6) forms of music instruction included music making through worship/praise team (non-choir), music therapy sessions, and music theory classes.

Figure 2

Music Instructional Approaches

Note. N = 44.

As depicted in Figure 2, involvement in Dance/Movement activities (34.09%, n = 15) emerged as the second most prevalent delivery of music instruction. Although not as common as Dance/Movement, Musical Theatre (25%, n = 11) was more popular than participation in both band and orchestra combined.

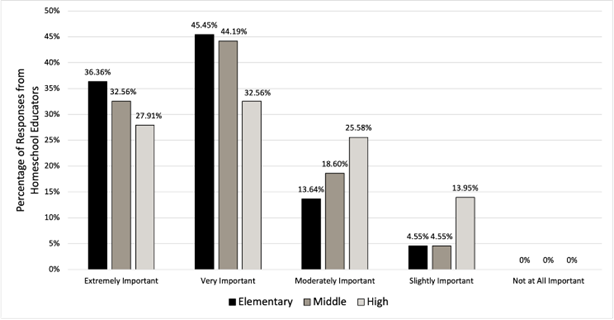

In responding to the inquiry on the importance of music education to an overall homeschool curricula, 81.81% (n = 36) of the respondents consider music education extremely important or very important in elementary grade levels (K-5 grades), as shown in Figure 3. For middle school students (6-8 grades), 75% (n = 33) responded that music education is extremely important or very important, with that percentage lowering to 59.09% (n = 26) for high school students (9-12 grades). In both the elementary and middle school levels, 4.55% (n = 2) of respondents suggested music education is only slightly important, with 13.63% (n = 6) for high schoolers. No respondents (n = 0) indicated that music education is not at all important at any grade level.

Figure 3

Importance of Music Education by Grade Levels

Note. N = 44.

When directly asked whether the role of music education varies according to student grade level, 25 teachers (56.82%) responded affirmatively, while the remaining 19 teachers (43.18%) indicated that the role of music education within the overall curriculum does not change with grade level.

To understand homeschool educators’ opinions on the value of music education, we invited open-ended responses for each of the two latter questions. These qualitative remarks correspond with the quantitative data, providing some insight on why the educators include music opportunities for their students. One teacher responded: “I believe music education to be extremely important for the purpose of personal development, even if the student does not have a strong interest in music as a vocation. Music is primary to life.” Another participant elaborated on the role of music education at different age levels:

I believe all elementary students should have music education and the option to choose to learn an instrument. Music helps brain development in my opinion. This should continue through middle school. Music in high school should start to follow an optional course. Not all students enjoy or wish to learn about music and hopefully had exposure earlier. It should be available and encouraged, but not mandatory.

This perspective is supported by another educator: “My philosophy is to establish a foundation of music in the elementary years. Once they reach middle school and high school, they may pursue it further if it is their passion.” The data indicated that homeschool teachers view music instruction as essential for students’ cognitive and personal development, with others also considering music to be a fundamental aspect of life.

Discussion

The structure of this discussions centers around the two research inquiries that informed this study: (1) the music-related activities and instructional approaches implemented for homeschool music education, and (2) the perspectives of homeschool educators concerning the role of music education within their broader academic curriculum. Following independent and collaborative coding of the quantitative data and open-ended questions, three themes emerged that address research question one: (1) student agency, (2) integration of music instruction within other subject areas, and (3) financial barriers to accessing musical resources. In relation to the second research question, data indicated that homeschool educators view music education as a valuable subject in their overall curricular offerings. Comparing our data to the related literature confirmed parallel findings.

Regarding music-related activities and instructional approaches, this study corroborated the research of Young (1999), who found that singing and individualized music instruction are frequent in the music education of homeschool students. The majority of participants in the present study disclosed that singing (79.54%, n = 35) was the most common music-related activity; however, fewer reported participation in choir, individual voice lessons, or another organized delivery of group singing, such as worship/praise team. The researchers were unable to wholly address this divergency without additional data. This discrepancy may have occurred because singing in some homeschool settings functioned as an informal activity rather than as part of structured instruction. Murphy (2021) discussed differences in formal versus informal learning within the homeschool environment. Along these lines, singing as a musical activity may have taken place alongside recordings and websites that provided opportunities for musical expression but did not necessarily offer formal instruction. As Young (1990) asserted, “The perspective of home schooling parents in regard to what constitutes music education may be different than that of the profession” (p. 121).

The second most common music-related activity was Performing on instruments, alone and/or with others (65.91%, n = 29). A relationship between this activity and the instructional delivery of Individual Piano Lessons (65.91%, n = 29) seemingly existed. An additional 31.82% (n = 14) of respondents marked that students engage in individual instrument lessons other than piano. Myers (2010) found that of her 43 participants – a comparable number of respondents to this study – private lessons on keyboard, voice, or stringed instruments was most common.

Although the survey did not specifically address individual string instrument lessons, only 2.27% (n = 1) of respondents indicated student participation in an orchestra. This lower level of participation may have been due to a lack of ensemble accessibility for these homeschools. At the time of data collection, the researchers were aware of only two options for orchestral participation: (1) a small string orchestra affiliated with a homeschool, which has since been discontinued, and (2) a costly, audition-based youth orchestra administered by a regional professional orchestra.

Nichols (2012) and Parker (2012) reported that homeschool students participated in traditional group ensembles, including choir, band, and orchestra, but data of the current study revealed lower level of involvement in group music ensembles. This divergency may be attributed to the limited availability of community-based ensemble opportunities for homeschool students in the geographic area covered by the current study. Additionally, Indiana state legislation does not require public schools to admit homeschool students for classes or extracurricular involvement. Therefore, each public school or school district may or may not allow homeschool student participation in music ensembles. With no state-level law granting permission for involvement, this might dissuade homeschool educators from seeking group ensemble involvement through local public schools.

Although participation in choir, band, and orchestra was lower than anticipated, there was a notable presence of engagement in Dance/Movement activities and Musical Theatre. These forms of artistic involvement may have offered homeschool students opportunities for creative expression and collaborative experiences comparable to those typically found in traditional ensemble settings. Moreover, musical theatre classes may inherently incorporate various elements of music education—such as singing, listening, evaluation, and performance—that align with the National Standards for Music Education, though these music-related activities may not have been fully reflected in the collected data.

Even though quantitative data concerning music-related activities and instructional approaches offered limited information on the curricula of homeschool music education, the open-ended responses provided additional insight. One pedagogical approach common amongst the participants was student agency in music curricular decision-making. Homeschool educators spoke about student interest and talent as major factors in determining their children’s music education. One participant shared:

I believe the role of music education – beyond general music education and exposure which could be taught in the elementary grades – depends more on the natural ability and interest of each student. Some students of any age receive enough benefits from music appreciation, and some students of any age who have shown interest/talent would receive greater benefits from more intensive music education such as age-appropriate instrument lessons and theory.

Another respondent offered, “Music as part of general education is great, but the importance of more intensive music education (such as music theory or instrument/choir performance) for each child will be addressed individually based on their interest and ability.” In regards to providing student agency in music instruction, one educator provided, “The opportunity should be there to play an instrument, but it should not be forced; the child should be able to choose their own music at least part of the time.” Another teacher reiterated this notion by commenting, “I believe all elementary students should have music education and the option to choose to learn an instrument; not all students enjoy or wish to learn about music – it should be available and encouraged, but not mandatory.” The data suggested that, to some extent, homeschool teachers permitted students to selected how they engaged in music based on individual interest.

Homeschool educators spoke about the inclusion of music in other school subject areas. One teacher suggested, “It can/should be studied as part of history, math, reading, art, etc.” Another participant similarly responded, “It should be incorporated into the study of math, other arts, history, and culture, and not a stand-alone entity.” Additionally, an educator shared:

Educators should not teach in silos. In real life we don’t live in compartments. We use math in cooking, we use art in decorating our homes, we use physics in driving or fixing our cars. Why teach in compartments? If music is your discipline, incorporate the study, appreciation, application and use into all overlapping disciplines.

One teacher disclosed that music is “not central” to the overall education of a child, but music “can be included in all areas of learning.” These responses suggested that homeschool teachers incorporate music through the teaching of other subjects, but that music does not need to be a standalone discipline.

This study highlighted the financial barriers some homeschools faced for access to music instruments, equipment, and other music education resources. While a student in a public, private, or charter school may have access to costly classroom materials, and the option to borrow a school-owned instrument, a homeschool student might lack similar access. One homeschool teacher commented, “Music is a huge component of a quality education experience,” however they disclosed, “I always struggled to find quality, affordable experiences for my six homeschooled children.” Another respondent shared that students in their homeschool were not involved in any formal music instruction because “money is always an issue.” One educator mentioned that “time and money are two crucial factors” to the inclusion of music education in their curricula. Such responses supported Hamlin’s (2019) assertion that the cost of expensive instruments and music equipment prohibited some homeschool students from receiving a comprehensive or varied music education. Despite the financial concerns expressed by some participants, the data revealed that individual music lessons (piano, voice, or another instrument) continued to be a prevalent form of music instructional delivery.

In response to the second research question, the data indicated that homeschool educators regarded music as an integral component of a homeschool student’s education. When prompted about the role of music education in a student’s overall educational experience, one participant offered, “I believe music education to be extremely important for the purpose of personal development.” Another teacher responded, “Music allows our minds to think creatively, soothes anxiety, and involves math. It helps to study music throughout your whole life!” Homeschool educators recognized the value of music for its therapeutic purposes, creativity, and its contributions to cognitive development. It remains uncertain whether homeschool educators placed value on a comprehensive music education comparable to that typically offered in public schools. Furthermore, the data did not reveal whether the integration of music into other subject areas or individual music instruction was considered sufficient by homeschool teachers to meet the music educational needs of their students.

Offering a perspective on what should be included in music education and how it should be implemented, one teacher summarized, “There should be exposure to a wide range of styles and time periods, the best of the best, and it should be enjoyed in multiple settings, at home, outdoors, concerts, musicals, theater.” This passage offered a viewpoint likely similar to many music educators in all settings, of all ages. Overall, this study suggested homeschool teachers believed students need a high-quality music education that explores varied repertoire in and beyond a classroom environment. As one home school teacher affirmed: “Music is universal and should be studied by all!”

Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to understand the music-related activities and instructional approaches that encompassed music education in homeschools. Data suggested that homeschool educators valued and included music in their student’s education, despite the curricular autonomy permitted by Indiana state law. Based on participants’ self-reported music-related activities and instructional approaches, individual music lessons in piano, voice, or other instruments emerged as the most prevalent form of musical engagement. There seemed to be gaps in the music curricula of some homeschool students who may have lacked opportunities to be involved in music ensembles (i.e., band, choir, orchestra) or who received fewer opportunities to compose, analyze, and evaluate music. Although participation in music ensembles was lower than expected, involvement in dance/movement activities and musical theatre exceeded expectations. Homeschools in the geographic region of this study may benefit from increased access to music education resources and support, thereby enabling students to engage in a broader range of music-making experiences.

In a brief 1997 article published in the Music Education Journal, two music educators engaged in a respectful debate regarding whether public schools should permit homeschool students to participate in music classes and ensembles (Williams & Guenzler, 1997). One author advocated for the inclusion of homeschool student musicians in public school music programs, whereas the opposing perspective argued that such inclusion could potentially reduce musical opportunities available to public school students. Based on findings of the current study, homeschool students may benefit from participation in public school music ensembles. The authors’ position on this debate aligns with Nichols’s (2012) inquiry, who posed the question: “If we, in the parlance of our professional organisations, hold fast to the idea of ‘music for all,’ are we then prepared to offer meaningful music opportunities to all, regardless of their mode of schooling?” (p. 124). This perspective offers valuable insight for the National Association for Music Education and other professional organizations, such as the Music Teachers National Association and the National Association of Teachers of Singing, as they consider inclusive practices that reflect their stated commitments to equitable access in music education.

Based on the response rate and participant size, this study is ungeneralizable; however, it contributes to the related literature by offering new findings and supporting the results of other researchers. Replication of this study on a national scale possibly provides crucial data on how state and local regulations impact homeschool music education. Future studies might also further investigate informal versus formal music instruction in homeschools or examine homeschool educators’ perspectives on involvement in public school music classes. With an estimated 3.135 million students in homeschools (Ray, 2022), and with researchers estimating growing numbers in forthcoming years, music educators, music teacher educators, and professional organizations are encouraged to consider how they can provide greater support to homeschool teachers and students.

References

Anders, J. T. (2023). Parental perspectives of homeschooling music education curricula (Publication No. 30526162) [Doctoral dissertation, Boston University]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses.

Blakeslee, M. (Ed.). (1994). Dance, music, theatre, visual Arts: What every young American should know and be able to do in the arts: National standards for arts education. Music Educators National Conference.

Campbell, P. S., & Scott-Kassner, C. (1995). Music in childhood: From preschool through the elementary grades. Simon & Schuster Macmillan.

Davis, A. (2013). Evolution of homeschooling. Distance Learning, 8(2), 29–35.

Fehrenbach, P. (1995). Music in home education: A creative approach to understanding music. Home School Researcher, 11(2).

Gaither, M. (2008). Why homeschooling happened. Educational Horizons, 86(4), 226–237.

Guhn, M., Emerson, S. D., & Gouzouasis, P. (2020). A population-level analysis of associations between school music participation and academic achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 112(2), 308–328. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000376

Hamlin, D. (2019). Do homeschooled students lack opportunities to acquire cultural capital? Evidence from a nationally representative survey of American households. Peabody Journal of Education, 94(3), 312–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/0161956x.2019.1617582

Hille, A., & Schupp, J. (2015). How learning a musical instrument affects the development of skills. Economics of Education Review, 44, 56–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2014.10.007

Houston, D. M., Peterson, P. E., & West, M. R. (2023). Parental anxieties over student learning dissipate as schools relax anti-COVID measures: But parent reports indicate some shift away from district schools to private, charter, and homeschooling alternatives. Education Next, 23(1), 20–27.

Hyde, K. L., Lerch, J., Norton, A., Forgeard, M., Winner, E., Evans, A. C., & Schlaug, G. (2009). The effects of musical training on structural brain development: A longitudinal study. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1169(1), 182–186. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04852.x

Indiana Department of Education. (2021, July 21). Homeschool information for parents and guardians: Frequently asked questions. https://www.in.gov/doe/files/Homeschool-FAQ-v2.pdf

Jamison, P., Meckler, L., Gordy, P., Morse, C. E., & Alcantara, C. (2023, October 31). Home schooling’s rise from fringe to fastest-growing form of education. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/interactive/2023/homeschooling-growth-data-by-district/

Jaschke, A. C., Honing, H., & Scherder, E. J. A. (2018). Longitudinal analysis of music education on executive functions in primary school children. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 12, Article 103. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2018.00103

Kinney, D. W. (2008). Selected demographic variables, school music participation, and achievement test scores of urban middle school students. Journal of Research in Music Education, 56, 145–161. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022429408322530

Levitin, D. J. (2007). This is your brain on music. New American Library.

Murphy, A. M. (2021). Homeschool music education: A descriptive study (Doctoral dissertation). Digital Repository at the University of Maryland.

Murphy, J. (2013). Riding history: The organizational development of homeschooling in the U.S. American Educational History Journal, 40(2), 335–354.

Myers, S. L. (2010). Homeschool parents’ self-reported activities and instructional methodologies in music (Master’s thesis). ProQuest, Ann Arbor.

Newberry, L. (2022, January 24). More parents are home-schooling. Some are never turning back. Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/california/newsletter/2022-01-24/8-to-3-homeschooling-on-rise-8-to-3

Nichols, J. (2005). Music education in homeschooling: A preliminary inquiry. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, (166), 27–42.

Nichols, J. (2012). Music education in homeschooling: Jamie’s story. In M. S. Barrett & S. L. Stauffer (Eds.), Narrative Soundings: An Anthology of Narrative Inquiry in Music Education (pp. 115–125). Springer Dordrecht.

Pannone, S. (2015). Homeschool curriculum choices: A phenomenological study. Home School Researcher, 31(3).

Parker, E. C. (2012). An intrinsic case study of two homeschooled undergraduates’ decisions to become and remain music education majors. Journal of Music Teacher Education, 21(2), 54–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/1057083711412782

Ray, B. D. (2022, September 15). How many homeschool students are there in the United States during the 2021–2022 school year? Retrieved July 15, 2023, from https://www.nheri.org/how-many-homeschool-students-are-there-in-the-united-states-during-the-2021-2022-school-year/.

Silverman, M. (2011). Music and homeschooled youth: A case study. Research Studies in Music Education, 33(2), 179–195. https://doi.org/10.1177/1321103X11422004

Williams, K. E., & Guenzler, R. (1997). Point counterpoint. Music Education Journal, 83(6), 10–11.

Wiersma, W., & Jurs, S. G. (2009). Research methods in education: An introduction. Pearson.

Young, B. M. (1999). The music education of home-schooled students in Broome County, New York (Doctoral dissertation). UMI Company, Ann Arbor, MI. ¯