Home School Researcher Volume 40, No. 1, 2026, p. 1-10

(Volume 40 was originally scheduled to be published in 2024.)

Professor of Economics, Department of Economics and Finance, University of Louisiana at Lafayette, Lafayette, Louisiana, c00257165@louisiana.edu

Wesley Austin

Associate Professor of Economics, Department of Economics and Finance, University of Louisiana at Lafayette, Lafayette, Louisiana, wesley.austin@louisiana.edu

Joby John

Dean, Professor of Marketing, College of Business, Lamar University, Beaumont, Texas, jjohn9@lamar.edu

Abstract

Homeschooling has grown in recent years. In percentage terms, the number of homeschooled students has grown much faster than private-school or public-school enrollments. This study investigates factors that affect the choices families make between homeschooling and two alternatives: public and private schools. The current study employs a logit regression analysis utilizing data from the 2019 National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), Parental and Family Involvement in Education (PFI), which is a nationally representative survey of 16,446 respondents (of which about 4% report homeschooling children). We find significant effects associated with total family income, educational attainment of the child’s parents, religious orientation, and “family cohesion” as measured by the number of times families eat meals together.

Keywords: Home education, homeschool, schooling, education, school choice.

Homeschooling predates public schooling in the United States, yet it has recently emerged as “the new kid on the block,” quantitatively speaking. The number of homeschooled children in the US increased from approximately fifteen thousand in the 1980s to an estimated two million before the COVID-19 pandemic in 2019 (Cheng & Hamlin 2023). Homeschool students represented only about 0.03% of U.S. school-age children in the mid-1970s but had grown to 3.4% in 2012 – a 113-fold growth occurred over roughly four decades (Ray, 2017b, p. 605). Homeschooling is growing in the United States (Smith & Watson 2024) and becoming more diverse racially (Bjorklund-Young & Watson 2024). The present paper addresses why parents choose to homeschool and examines factors that drive the choice among public, private, and homeschool options.

Research has consistently shown that school choice is partly driven by objective elements informing choice in a cost-benefit context such as income, tuition, fees, taxes, time constraints, etc. (Houston & Toma, 2005). Research has also identified a broader array of factors, including various sociological, political, and ideological considerations (Gaither 2008; Isenberg 2007; Kunzman & Gaither 2020). Recent trends in school choice indicate that fundamental societal attitudes toward public schools are shifting. Specifically, there is evidence that families are beginning to feel that their religious or cultural values are being undermined by “political correctness,” “woke” school policies (Greene & Paul 2022), and elitist values and expertise (Maranto, 2021; Singer, 2021),

The present study reexamines factors that have been shown to affect school choice generally, and particularly the decision to homeschool. We employ a logit regression analysis of determinant factors drawing upon extensive 2019 National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) data on parental involvement in education (Hanson & Pugliese 2019). This data provides a wealth of information on family characteristics such as race, religious orientation, and time spent in family activities, which opens windows into preferences that lie beyond the traditional objective “economic” determinants of school choice, such as income and tuition. Our analysis focuses on the family and yields probabilities that a child is homeschooled as a function of various family characteristics. Results are consistent with the conjecture that total family income, educational attainment of the child’s parents, and religious orientation are important determinants of school choice. This study also finds some evidence that households with a strong preference for family cohesion are drawn to homeschooling.

We begin with a review of the literature on school choice, focusing on the homeschooling option, followed by sections on data and the empirical model, discussion of results, and summary with suggestions for future research.

The Economics of School Choice, A Focused Review of the Literature

Research into school choice has grown, one might say flourished, over the last 50 years. In the 1980s and 1990s, research focused on the choice between public versus private schooling. More recently, research on school choice includes homeschooling as a third option. The literature on homeschooling is voluminous (for comprehensive surveys, see (Gaither, 2017; Green & Hoover-Dempsey, 2007; Kunzman & Gaither, 2020; Maranto & Bell, 2018). Few researchers have grounded their investigations in formal economic models of school choice. Notable exceptions are Houston & Toma (2003), and Isenberg (2002; 2006; 2007). Their analyses are explicitly economic: the household considers the benefits and costs of schooling alternatives, both implicit and explicit, and chooses the option that provides the greatest utility, subject to budgetary and time constraints. We begin our literature review with these models of school choice because they offer theoretically comprehensive models of choice, rather than a narrow focus on specific factors of choice. Also, they provide a useful way to categorize the various factors in terms of family and/or school characteristics. While these researchers take slightly different formal approaches, they arrive at similar sets of choice determinants – essentially the same determinants that appear in the broader body of research on school choice and homeschooling in particular.

The household utility function proposed by Houston & Toma (2003) contains a vector of attributes representing the household’s socioeconomic characteristics, a vector of attributes on which households evaluate the quality of schools, and a composite package of consumer goods. Household characteristics that may affect school choice include the mother’s and father’s income and education levels, race and ethnicity, marital status, and religious-taste variables. School attributes relate primarily to academic quality in this model. Consumer goods enter the equation because school costs, especially tuition at private schools, deplete the household budget available for the consumption of other goods. Each household allocates its resources among schooling and all other goods and services, choosing the type of education (public, private, or home) that generates the greatest household utility. In similar fashion, Isenberg (2006) proposes a utility function comprising household characteristics, school characteristics, and a composite of consumer goods. The principal differences between the two models are that Isenberg includes the mother’s leisure time explicitly and accounts for various school and household characteristics through their effects on the production of ‘child quality.’ Household characteristics (e.g., the presence of other adults) can also affect the quantity of the mother’s leisure time in Isenberg’s approach.

While the two models differ formally, they include common factors discussed in a large and growing body of literature on school choice, including homeschooling. Given the growing importance of homeschooling in the school choice equation, the following review emphasizes research on that option.

Income and Earning Potential

Stay-at-home mothers teach the majority of homeschooled children in two-parent, heterosexual families with a father supporting the family in the paid labor force (Aurini & Davies, 2005; Isenberg, 2002; Lois, 2013; Murphy, 2012; Stevens, 2009). Therefore, household characteristics relevant to school choice are defined in no small measure by the socioeconomic standing of the mother. Another important factor is the potential for market employment. Homeschooling precludes or greatly limits the mother’s participation in the labor force, which imposes an opportunity cost of lost earnings. The greater the woman’s potential earning capacity, the greater the cost.

The father’s earnings affect the two-parent household’s monetary budget. Higher earnings could generate an income effect – positive or negative – on the “demand” for different types of schooling. In the parlance of economics, the question is whether homeschooling and private schooling are “inferior” or “superior” goods. Isenberg discusses two opposing effects of an increase in income. Additional income would expand the household money budget and possibly the time budget. In this case, the income effect would increase the probability of homeschooling “just as they increase the probability of staying home with preschool children” (Isenberg, 2002, p. 4). However, he also suggests that income might generate a backward-bending (i.e., inferior goods) effect on homeschooling “due to the alternative of ‘purchasing’ higher school quality” at superior private schools (p. 4). Based on NHES data, Isenberg concludes that private schools are superior goods. Specifically, “those who have the [financial] means to escape poor quality public schools prefer to do so by exit strategies of sending their children to better schools rather than by … homeschooling” (p.15).

Parents’ Education

Generally speaking, earning capacity positively correlates with education, suggesting that more highly educated women are less likely to homeschool due to the greater opportunity cost of lost earnings (Isenberg, 2002). However, the mother’s education could also affect her productivity as a homeschool teacher. If the quality of homeschool education improves with higher education levels, the homeschool option becomes more attractive (Isenberg, 2002, p. 16). The household must weigh the marginal benefits of labor force participation versus the gains through better homeschool education.

Houston & Toma (2003) find evidence that the mother’s educational attainment positively influences the decision to homeschool – to a point. Specifically, “the rising productivity of effort associated with providing homeschooling outweighs the increased value of labor force participation with high school and some college, but reverses with a college degree” (p. 930). Isenberg (2007) found that incremental increases in the mother’s education level from less than high school to a college degree improve the probability of homeschooling by 1.4% (p. 403).

The father’s level of education is an important household characteristic as well. Higher levels of education typically lead to greater earnings and a larger household budget. The father’s level of education can also affect the household’s educational tastes – the values and beliefs by which families judge the relative merits of public, private, and homeschooling. Houston & Toma (2003) find evidence that increases in the father’s level of education correlate negatively with the odds for choosing public schools over homeschooling when controlling for income.

Religion, Family, And Moral Instruction

Many studies have examined the desire for religious and moral instruction as motivations for homeschooling; not surprisingly, the findings are mixed. A 2019 NCES survey found that 59% of families reported a desire to provide religious instruction was a motivation for choosing to homeschool; 75% reported the desire to provide moral instruction; 73% cited dissatisfaction with academic instruction as a motivation; 80% cited concerns for the environment (crime, drugs, bullying) at schools; and 75% reported that emphasis on family life together was a motivation to homeschool (Hanson & Pugliese, 2019) . While families in recent years have expressed complex and changing motivations for homeschooling (Tilhou, 2020) , we may reasonably conclude that dissatisfaction with public schools’ ability to teach values and develop character is an essential motivation among homeschooling parents (Gaither, 2017; Kunzman & Gaither, 2020).

Christian fundamentalism motivates some homeschoolers, especially in promoting religious values and the centrality of the family (Kunzman, 2010) and resisting the homogenization of education in public schools (Burke, 2016; Neuman & Guterman, 2017). On the other hand, some households see homeschooling as a way to instill progressive or nonconventional values (Gaither, 2023; Neuman & Guterman, 2017). Houston & Toma (2003) find that a higher percentage of Catholics in the population increases the probability of choosing private schools relative to homeschools (p. 932). Their study did not identify Catholic with either progressive or traditional culturally. They found no significant effects for other religion variables. Isenberg reports that “a significant minority” of households homeschool for religious reasons. When families were classified as “very religious,” the probability of their homeschooling increased by 1.3% (2007, p. 403). He concludes that “religious families – particularly evangelical Protestants – are significantly more likely to homeschool” (2007, p. 401). Isenberg (2002) reported similar results for the percent Protestants in rural districts (p. 44).

Religious and moral preferences are often embodied in “family values,” cultural norms nurtured and passed along through the family unit. Batts et al. (2024) found that he preference for strong familial bonds motivates the choice to homeschool. In a study focused on Hispanic families who homeschool, they found that “preservation or reclamation of cultural heritage is the most meaningful result of the decision to homeschool. Specific aspects of culture found are family cohesion, familial language, and living the values of a strong work ethic and the need to be resourceful” (2024, from the Abstract). They quote one participant who related family cohesion with homeschooling by emphasizing the importance of keeping one’s family close and spending time with family (2024, p. 598).

Nonmonetary Resources

Family characteristics besides education and income can affect the homeschooler’s instructional efficiency. The presence of older children and adults can increase instructional efficiency through a division of labor and possibly also free up time for leisure activities. Isenberg (2007) found that the probability of homeschooling increases by 0.5 percent for every additional adult in the household (p. 403). Households enhance instructional efficiency and economize in the expenditure of time through the use of technology and community resources such as libraries and homeschool support groups (Abuzandah, 2021; Cheng & Hamlin, 2023; Drenovsky & Cohen, 2012; Elsamanoudy & Mostafa, 2021; Gann & Carpenter, 2018; Lips & Feinberg, 2008). Isenberg’s 2007 model treats leisure time quantitatively in the context of the time budget. In utility terms, both the quantity and quality of leisure time matter. Studies have shown that stress and burnout are potential issues for those who provide homeschooling (Calear et al., 2022; Cuadrado et al., 2022; Heers & Lipps, 2022). To the extent that homeschool providers learn how to mediate negative stress factors through technology and other resources, they can not only expand the family time budget but derive more utility from leisure time.

Race

A growing body of research looks at race as a determinant in school choice (Ali-Coleman, 2022; Cheng & Hamlin, 2023; Fields-Smith & Williams, 2009; Williams-Johnson & Fields-Smith, 2022; Ray, 2015). For thorough recent reviews of the literature on Black homeschooling (Baker, 2024; Johnson, 2024). Minority households are turning to homeschooling. Between 2012 and 2016, the number of African Americans homeschooled in the US decreased, while the number of Hispanics increased (Hirsch, 2019). Analysis of the National Household Education Survey suggests that the percentage of homeschoolers who are people of color has increased. modestly, from 25% in 1998–99 to 29% in 2022–23, suggesting less diversity than public school students but similar to the private school population. However, the Household Pulse Survey suggests more racial diversity in modern homeschooling, with 40% of homeschoolers being students of color (Bjorklund-Young & Watson, 2024).

Regarding African-American households in particular, some research indicates that “educational protectionism,” or the desire to shield children from racist experiences they might encounter at public or private schools, features prominently in the choice for homeschooling (Mazama & Musumunu, 2014). Other research finds little evidence of such a motivation (Ray, 2015). Houston & Toma (2002) find that the percentage of Black families in the population is positively related to the probability of homeschooling (p. 932). However, Isenberg (2002) finds some evidence of the opposite relationship between race and public schooling (p. 42).

Academic Quality

Academic quality is major consideration in school choice. While we do not include this factor in our empirical analysis, it warrants discussion here. The quality of homeschooling has received considerable scrutiny in recent years (Bennett et al., 2019; Cogan, 2010; Coleman, 2014; Drenovsky & Cohen, 2012; Green & Hoover-Dempsey, 2007; Lubienski et al., 2013; Morgan, 2012; Ray, 2000). Findings generally support the contention that homeschooling produces academic results equal or superior to public education, but results are somewhat mixed. In a comprehensive review of the empirical research Ray (2017) presents considerable evidence that homeschooling generates superior educational outcomes. However, Lubienski et al. (2013) found no compelling empirical justification for the claim that homeschooling is academically superior to public schools. While there is evidence that homeschooled students perform better than those in public schools in mathematics, the homeschoolers’ math scores are not as impressive as their language arts scores, which are markedly higher for homeschoolers (Coleman, 2014; Qaqish, 2007). A plausible explanation for this finding is that mathematics instruction requires a greater degree of specialized knowledge in the field than most homeschool parents possess.

One can measure the academic quality of alternatives to homeschooling in numerous ways, including expenditures per student, dropout rates, and performance scores in math, writing, and other skills. The volume of literature on the issue of measuring school quality is too vast to be explored here. See (Schneider, 2017; Monarrez & Chingos, 2020) for good overviews of the issues and literature. Houston & Toma (2003) found that increases in public school expenditures per student reduce the probability of homeschooling, while increases in the number of dropouts increase the likelihood of homeschooling. Isenberg (2007) reports that homeschooling is negatively related to school funding at the local level. He also reports that increased NAEP state math scores reduced the probability of homeschooling. Houston & Toma (2003) find strong evidence that dropout rates increase the probability of homeschooling relative to public schools, but results are mixed regarding homeschooling versus private schools. Public school expenditures per student reduce the probability of homeschooling relative to public schools, but results are inconclusive concerning private schools. Marks & Welsch (2019) examined homeschooling participation at the statewide and district level in Wisconsin. They found that higher district level homeschool participation is associated with lower district grade school test scores, lower expenditure per pupil, and a lower percentage of Catholic individuals living in the surrounding area.

In the final analysis, what matters to parents is not whether homeschooling is academically superior but whether parents believe it is. Parents who homeschool have a strong sense of self-efficacy for helping their children succeed and generally invest more work in realizing these goals than parents with low self-efficacy (Green & Hoover-Dempsey, 2007). Presumably, such parents are inclined to positively judge the academic quality of home instruction they provide relative to that of public and private schools.

Socialization

Socialization is another factor that deserves discussion here, even though it is not included in our empirical analysis. It bears remembering that public schools were established partly to socialize students, especially those of immigrant families (Davis, 2011). The effects of homeschooling on socialization is an important and extensively examined topic (Brown, 1997; Guterman & Neuman, 2017; Hamlin, 2019; Kitchen, 1991; Ray ,2013; Medlin, 2006). Neither Isenberg nor Houston & Toma provide direct empirical evidence on the effect of homeschooling on socialization. Groundbreaking work was done by Taylor (1985), who concluded that homeschooled children are not socially deprived. Kitchen (1991) evaluated homeschool versus public school students’ self-perception in personal security, peer popularity, academic competence, and familial acceptance. Homeschooled students scored higher on security, academic competence, and familial acceptance, while traditionally-schooled students scored higher on peer popularity. Guterman & Neuman (2017) examined three aspects of children’s emotional world – behavioral problems, depression, and attachment security. They found a lower level of depression among homeschooled children, no difference in attachment security, and mixed results on behavioral issues. Some research has looked at the ability of homeschooled children to succeed socially in higher educational settings (Duggan, 2009; Drenovsky & Cohen, 2023; Medlin, 2013; Ray, 2004). Drenovsky & Cohen (2023) conclude that homeschooled students did not have significantly different levels of self-esteem compared to students who were never homeschooled.

Summary

School choice is a multifaceted decision. The literature suggests that family characteristics are influential in the school choice decision. The following section presents our empirical analysis of selected family characteristics suggested by the literature review, and for which the NHES/PFI study provides meaningful data. Our analysis establishes correlations between corresponding variables, and the likelihood of choosing the homeschool option.

Data and Empirical Model

Our empirical model employs data from the National Household Survey on Education (NHES), sponsored by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), which is administered to approximately 35,000 civilian, non-institutionalized individual adults, chosen so that the survey application offers a nationally representative, random sample. The survey is self-administered by mail or via the Web and is conducted about every four years. The 2019 NHES data is representative of 5- to 17-year-old pupils in grades K to 12. More specifically, we utilize data from the PFI (Parent and Family Involvement in Education) from 2019; the PFI survey was completed for 16,446 students in grades K through 12. Further, given that this study focuses on specific family attributes and religiosity questions (see below), our sample is concentrated on the 7,092 respondents to these questions, with at least one child either homeschooled or in a public school, and on the 2,132 respondents with at least one child either homeschooled or in a private school (both religious and non-religious). The PFI data covers various other variables on demographics, perceived school characteristics, and family attributes such as income, race, religion, parents’ marital status, and how family time is spent. Many previous homeschooling studies have relied on smaller datasets that include local and school district-level variables but failed to include a broad range of demographic factors.

Of all respondents, 1,677 (approximately 10 %) report children attending private schools, while 532 (approximately 4%) report Homeschooled as the type of school their children attend. The most prominent reasons cited for homeschooling were concern over school safety, such as drugs and negative peer pressure; dissatisfaction with academic instruction in other schools; and desire to provide religious/moral instruction.

In our PFI sample, the following select descriptive statistics were revealed: approximately 75% of families report eating the evening meal together four or more days in the past week, while about 50% report attending a religious or community event together in the past month. Approximately 57% of “first” parents or guardians (the first person responding to the survey is designated the “first parent,” the second to respond is the “second parent) received some education beyond high school graduation, while approximately 15% are Black/African American and 71% are White/Caucasian.

Model Specification

Vectors of family and school attributes affecting school choice are represented in the following logit model. School Choice Decision = α + β1Family Attributes + β2Religiosity/Family Cohesion + ε

School Choice Decision is a dichotomous variable in two choice situations, first, as a choice between homeschooling versus public schooling; and second, as a decision between homeschooling versus private schooling. Homeschooling is defined as education provided by a child’s parent(s)/guardian(s). Family Attributes are explanatory family-related variables that plausibly affect the school choice decision. Religiosity/Family Cohesion are explanatory variables related to religious orientation of the family as well as an indicator of how family time is spent, and ε is the error term. The α’s and β’s are parameters to be estimated. The analysis allows us to calculate the effects of various factors on the probability that a particular school option will be chosen.

The logit model satisfies the primary assumptions required for valid estimation and inference. The dependent variable denotes parents’ school choice, coded as a binary variable indicating whether the household selected homeschool, a private or public school for their child. This dichotomous structure aligns with the basic requirement of logistic regression for a binary outcome variable. The independent variables include both continuous (e.g., household income, parents’ education level) and categorical predictors (e.g., race, marital status), all of which were properly specified and dummy coded where necessary to ensure interpretability.

The assumption of independent observations is satisfied, as each observation in the dataset represents a unique household’s decision. There are no repeated measures or clustered data, reducing the likelihood of correlated residuals or dependence across variables. The data also satisfy the assumption of no multicollinearity, verified through Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values below 5 for all predictors, indicating that no independent variable is highly correlated with another.

The model was further examined for influential outliers and leverage points using standardized residual analysis. All values were within acceptable limits, confirming that no individual observation exerted undue influence on the regression estimates.

Finally, overall model fit was assessed using pseudo-R² statistics (Cox-Snell), and likelihood ratio (Estrella). The results indicate that the model provides an adequate fit and properly explains some variation in parental school choice behaviors. These diagnostic tests indicate that the logistic regression model meets all key assumptions, supporting the dependability and validity of the estimated relationships.

Family Attributes

Total Household Income is a binary variable categorized to represent families whose annual income is below $100,00 versus family income equal to $100,000 and greater.

Educational Attainment of Child’s First Parent or Guardian is a binary variable where the child’s first parent is either a college graduate or not. The distinction between “first” and “second” parent is essentially procedural. The first person responding to the survey is designated the “first parent,” the second to respond is the “second parent.”

The database contains several binary variables related to the child or child’s home, including the following that we employ, Family Type with Parents (2 Parents W/ Siblings); First Parent or Guardian Marital Status (Now Married); First Parent or Guardian Race (White); Second Parent or Guardian Race (White).

Religiosity/Family Cohesion

Several variables were listed in the survey in which parents could state motivating factors, in no particular order of importance, for selecting a type of schooling or not. As noted below, these variables often ranked “importance” of the factor from not important to great importance.

Reason for choosing school – Religious orientation is a binary variable categorized to represent families that place importance/great importance on religion in education versus those that place little/no importance on said religiosity.

Also, “family cohesion” binary variables are included, In the Past Week, Number of Times the Family Has Eaten the Evening Meal Together (4+ Times); Family Attended a Religious Event in The Past Month, a “religiosity” variable that captures whether or not the family has attended any religious function within the past 30 days.

Results

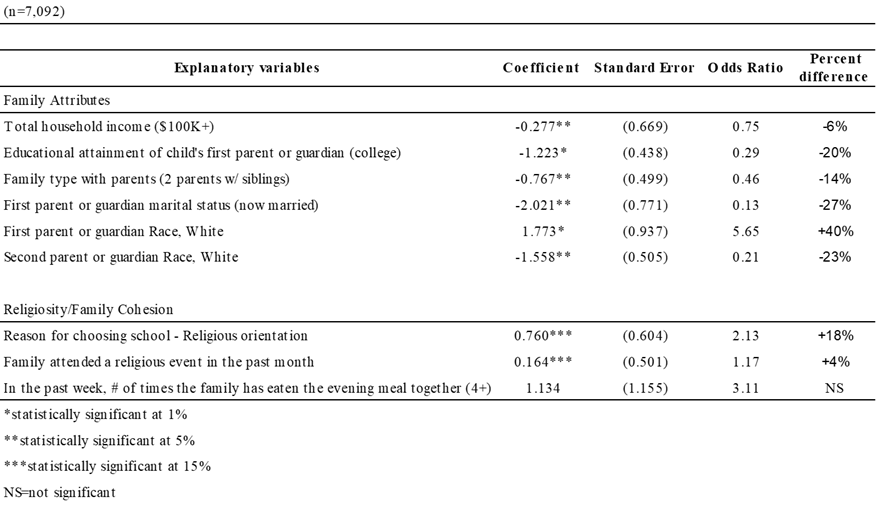

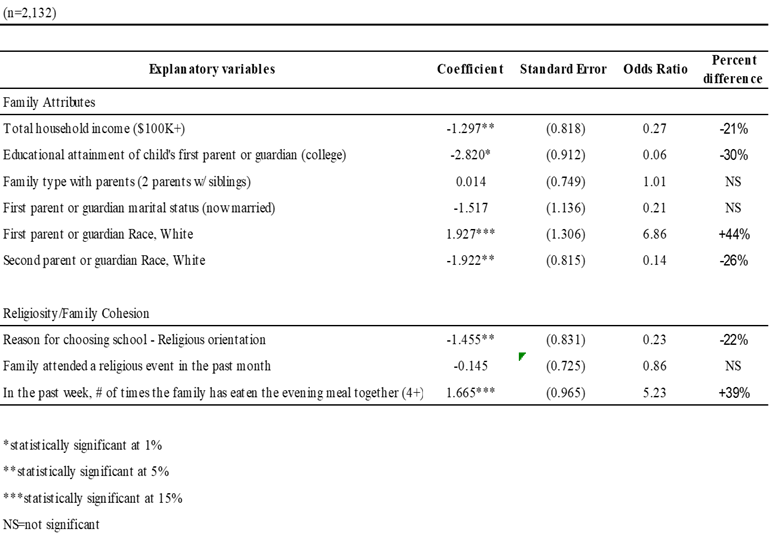

We summarize our findings in the following tables. Overall, for the model, the pseudo-R2 is 0.311 and the likelihood ratio is 0.268. The first table shows select descriptive statistics. The second table presents results for homeschooling versus public schooling, and the second table for homeschooling versus private schooling.

Table 1

Logit Regression Estimates for Selecting Homeschooling Over Public Schooling

Table 2

Logit Regression Estimates for Selecting Homeschooling Over Private Schooling

Discussion of Main Findings

Total Family Income: Greater total family income reduces the probability of homeschooling relative to public and private schooling, with differences of 6% and 21%, respectively. The negative association between homeschooling and family income indicates that homeschooling appears to be an “inferior good,” in economic parlance. Further, this negative link is consistent with the notion that homeschooling imposes an opportunity cost in the form of forgone earnings, assuming the would-be homeschool provider contributes to family income.

Results indicate that First Parent or Guardian (Now Married) decreases the probability of choosing homeschooling over public schools, despite the argument that having a spouse expands the homeschool instructor’s time budget. Family Type (2 Parents and Siblings) also decreases the probability of choosing homeschooling over public schools. As discussed above, the presence of multiple children in the household could lead to homeschooling efficiencies through a division of labor. Furthermore, if the fixed costs of homeschooling were significant, additional children might reduce the average cost (per child) of homeschooling. However, an opposing factor is that total homeschooling costs would increase with the number of siblings if all are homeschooled. Such “marginal sibling costs” might be less for public schooling, thus encouraging families to choose public schools over homeschooling. Results for homeschooling versus private are not significant with either of these family factors, i.e., neither decreases the likelihood of homeschooling relative to private schooling. One might expect this result if marginal sibling costs of private education are comparable to homeschooling. The marginal sibling cost effect might not operate as strongly when the choice is between homeschooling and private schooling.

The first parent’s Educational Attainment (College Degree) is inversely related with choosing homeschool over public and private schooling; the probability of homeschooling over public schools decreases by 20%, and the likelihood of choosing homeschooling over private schools is reduced by 30%. These results are not inconsistent with conclusions reached by Houston and Toma (2003), namely, that the advantages education brings in the form of increased productivity in providing homeschooling are effective up to a point but are outweighed by labor force considerations at higher levels of education.

Results for race are curiously contradictory. Regarding First Parent or Guardian Race, White, the influence is positive and significant for both choice options, yet negative and significant with regard to the second parent. In other words, if the first parent is White, the student is more likely to be homeschooled relative to both public and private schooling, but the opposite is true if the second parent is White. The data does not indicate whether the parents are of the same race. Two facts have been fairly well established in other studies (Bjorklund-Young & Watson, 2024): Whites account for a greater percentage of homeschooled students than do non-Whites; however, the percentage of homeschooled children who are non-White is growing. These facts do not explain the contradictory results for “first” and “second” parents. Unfortunately, our analysis offers little additional insight into the influence of race on school choice.

An important question is whether ideological, cultural, and religious preferences play a role in the rise of homeschooling. In the present study, the positive likelihood between Religious Orientation and homeschooling reveals that families that place importance on religion in education have an increased probability of selecting homeschooling relative to public schools by 18%. If families see public schools as hostile to their religious beliefs and practices, the choice of nonpublic education is encouraged. However, this correlation decreases the probability of selecting homeschooling over private schools by 22%. This result does not necessarily contradict the evidence that religious considerations partly motivate homeschooling. In point of fact, many private schools in the U.S. are church-related. If religious considerations are more important to those who choose private schools than to those who choose homeschooling, the negative probability difference is understandable.

Family Attendance at Religious Events (Past 30 Days) is likely and positively r elated with the decision to homeschool and increases the probability of selecting homeschooling over public school by 4%. (The effect on choosing private schooling is not significant.) Family Attendance at Religious Events involves family togetherness as well as religious orientation. A more direct measure of family cohesion is In the Past Week, the Number of Times the Family Has Eaten the Evening Meal Together (4+). This factor is also positively correlated with homeschooling and increases the probability of choosing homeschooling over private schooling by 39%. (The results for homeschool versus public are not significant, although the sign is positive.) Taken together, these results may indicate that households with a strong preference for family cohesion are drawn to homeschooling.

Summary and Conclusions

The literature on school choice provides numerous empirical analyses of factors determining the selection of one type of schooling over another. This paper attempts to add modestly to this research effort by focusing on selected family characteristics. Employing a logit regression analysis utilizing data from the NHES (PFI-Parent and Family Involvement in Education), we are able to report the following general findings:

- Total Family Income indicates that homeschooling is an “inferior good” (in the economic sense). Earning capacity, especially for the parent providing homeschool instruction, imposes an opportunity cost for time spent in homeschooling. This fact might partly explain why income is negatively related to the probability of homeschooling.

- Educational Attainment of The Child’s Parents is negatively related to homeschooling in favor of private schooling. Education is positively related to income, and separating the two for explanatory purposes is an inexact proposition. We conclude that educated parents value education for their children, and those parents who can afford private schools are likely to choose that option.

- Family Type and Marital Status are significant factors in the choice between homeschooling and public schools, but not private schools. Married parents with more than one child are less likely to choose homeschooling over public schools, indicating that neither the presence of a spouse nor economies of scale in homeschooling are strong influences.

- Religious Orientation increases the probability of choosing homeschooling over public schools but decreases the probability of selecting homeschooling in favor of private schools. Family Attendance at Religious Events (Past 30 Days) increases the probability of selecting homeschooling over public schools, but not private. Taken together, these findings suggest that parents with strong religious values are unsatisfied with the influence of public education on religious values. Some of these parents choose homeschooling, and others (particularly those with higher levels of education and income) go with private schools.

- “Family cohesion” might be an underappreciated value in the decision to homeschool. Number of Times the Family Has Eaten the Evening Meal Together is positive and highly significant effect on the choice of homeschooling over private schooling. Other “family activity” variables are not significant, but of the supporting (positive) sign.

Evidently many parents feel that public schools fail to support and, in many cases, actively undermine traditional family values. In recent years, clashes between parent groups, school boards, and governmental regulations on matters ranging from school curricula regarding critical race theory and sex education in elementary school to non-binary gender policies in school sports or restrooms suggest that the trend toward private schools and homeschooling will become more pronounced and significant. If this is the case, subjective, values-oriented factors will become as important as traditional objective economic considerations, if not more so, in the analysis of school choice. Along such lines, future research is needed on “family cohesion” variables that capture the family’s propensity to spend time together in day-to-day activities such as evening meals, sports, arts and crafts, or religious events. A potentially fruitful approach would be to construct an index using principal component analysis and the variables in the PFI dataset and estimate the effect of the index on school-type choice. One could do something similar with the religiosity questions and combine the measures to create an index of religiosity.

An obvious area for future research is analysis of the effects of COVID. While not yet extensively addressed in school choice research, general research into these effects is rapidly expanding (Bubb & Jones, 2020; Calear et al., 2022; Fontenelle-Tereshchuk, 2021; Girard & Prado, 2022; Heers & Lipps, 2022; Hirsh, 2019b; Lapon, 2021; McCluskey, n.d.; Pensiero et al., 2020). Future data post-COVID from the NHES will facilitate research on the effects of COVID on homeschooling.

References

Abuzandah, S. A. (2021). Reasons for choosing homeschooling and approaches most used: A qualitative content analysis. Kansas State University.

Ali-Coleman, K. Z. (2022). BLACK EXCELLENCE. Homeschooling Black Children in the US: Theory, Practice, and Popular Culture, 199.

Aurini, J., & Davies, S. (2005). Choice without markets: Homeschooling in the context of private education. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 26(4), 461–474. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425690500199834

Baker, T. (2024). Socio-Historical and Contemporary Context of Black Home Education within the Black Belt of the American South. Journal of School Choice, 18(4), 554–571. https://doi.org/10.1080/15582159.2024.2422238

Batts, C., Carrillo Carrasquillo, M. H., Miranda Tapia, O. R., & Bass, L. (2024). “We Hold Culture in Our Hearts”: A Phenomenological Study of Hispanic/Latina Homeschool Experiences. Journal of School Choice, 18(4), 586–608. https://doi.org/10.1080/15582159.2024.2422244

Bennett, D. L., Edwards, E., & Ngai, C. (2019). Homeschool background, time use and academic performance at a private religious college. Educational Studies, 45(3), 305–325.

Bjorklund-Young, A., & Watson, A. R. (2024). The Changing Face of American Homeschool: A 25-Year Comparison of Race and Ethnicity. Journal of School Choice, 18(4), 540–553. https://doi.org/10.1080/15582159.2024.2422743

Brown, J. (1997). Parents’ rationale for homeschooling: A qualitative study [Masters Dissertation]. Youngstown State University.

Bubb, S., & Jones, M.-A. (2020). Learning from the COVID-19 home-schooling experience: Listening to pupils, parents/carers and teachers. Improving Schools, 23(3), 209–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/1365480220958797

Burke, L. M. (2016). Avoiding the “Inexorable Push Toward Homogenization” in School Choice: Education Savings Accounts as Hedges Against Institutional Isomorphism. Journal of School Choice, 10(4), 560–578. https://doi.org/10.1080/15582159.2016.1238331

Calear, A. L., McCallum, S., Morse, A. R., Banfield, M., Gulliver, A., Cherbuin, N., Farrer, L. M., Murray, K., Rodney Harris, R. M., & Batterham, P. J. (2022). Psychosocial impacts of home-schooling on parents and caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 119. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-12532-2

Cheng, A., & Hamlin, D. (2023). Contemporary Homeschooling Arrangements: An Analysis of Three Waves of Nationally Representative Data. Educational Policy, 37(5), 1444–1466. https://doi.org/10.1177/08959048221103795

Cogan, M. F. (2010). Exploring academic outcomes of homeschooled students. Journal of College Admission, 208, 18–25.

Coleman, R. E. (2014). The homeschool math gap: The data. Coalition for Responsible Home Education.

Cuadrado, E., Arenas, A., Moyano, M., & Tabernero, C. (2022). Differential impact of stay‐at‐home orders on mental health in adults who are homeschooling or “childless at home” in time of COVID‐19. Family Process, 61(2), 722–744. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12698

Davis, A. (2011). Evolution of Homeschooling. Distance Learning, 8(2).

Drenovsky, C. K., & Cohen, I. (2012). The impact of homeschooling on the adjustment of college students. International Social Science Review, 87(1/2), 19–34.

Drenovsky, C. K., & Cohen, I. (2023). THE IMPACT OF HOMESCHOOLING ON THE ADJUSTMENT OF COLLEGE STUDENTS.

Duggan, M. H. (2009). Is all college preparation equal? Pre-community college experiences of home-schooled, private-schooled, and public-schooled students. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 34(1–2), 25–38.

Elsamanoudy, A. Z., & Mostafa, R. (2021). Homeschooling using Technology Enhanced Learning as an adapting learning strategy during COVID-19 Outbreak. Academia Letters. https://doi.org/10.20935/AL1823

Fields-Smith, C., & Williams, M. (2009). Motivations, sacrifices, and challenges: Black parents’ decisions to home school. The Urban Review, 41, 369–389.

Fontenelle-Tereshchuk, D. (2021). ‘Homeschooling’ and the COVID-19 Crisis: The Insights of Parents on Curriculum and Remote Learning. Interchange, 52(2), 167–191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10780-021-09420-w

Gaither, M. (2008). Why homeschooling happened. Educational Horizons, 86(4), 226–237.

Gaither, M. (2017). Homeschooling in the United States: A review of select research topics. Pro-Posições, 28(2), 213–241. https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-6248-2015-0171

Gaither, M. (2023). Why Homeschooling Happened. Educational Horizons, 86(4), 226–237.

Gann, C., & Carpenter, D. (2018). STEM Teaching and Learning Strategies of High School Parents With Homeschool Students. Education and Urban Society, 50(5), 461–482. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013124517713250

Girard, C., & Prado, J. (2022). Prior home learning environment is associated with adaptation to homeschooling during COVID lockdown. Heliyon, 8(4), e09294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09294

Green, C. L., & Hoover-Dempsey, K. V. (2007). Why Do Parents Homeschool? Education & Urban Society, 39(2), 264–285.

Greene, J. P., & Paul, J. D. (2022). Time for the School Choice Movement to Embrace the Culture War. Backgrounder. No. 3683. Heritage Foundation.

Guterman, O., & Neuman, A. (2017). Schools and emotional and behavioral problems: A comparison of school-going and homeschooled children. The Journal of Educational Research, 110(4), 425–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2015.1116055

Hamlin, D. (2019). Do homeschooled students lack opportunities to acquire cultural capital? Evidence from a nationally representative survey of American households. Peabody Journal of Education, 94(3), 312–327.

Hanson, R., & Pugliese, C. (2019). Parent and Family Involvement in Education: 2019 (First Look / ED TAB No. NCES 2020076). National Center for Education Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2020076

Heers, M., & Lipps, O. (2022). Overwhelmed by Learning in Lockdown: Effects of Covid-19-enforced Homeschooling on Parents’ Wellbeing. Social Indicators Research, 164(1), 323–343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-022-02936-3

Hirsh, A. (2019a). The Changing Landscape of Homeschooling in the United States.

Hirsh, A. (2019b). The Changing Landscape of Homeschooling in the United States. Center on Reinventing Public Education.

Houston, R. G., & Toma, E. (2003). Home Schooling: An Alternative School Choice. Southern Economic Journal, 69(4), 920–935.

Isenberg, E. (2002). Home Schooling: School Choice and Women’s Time Use. National Center for the Privatization of Education.

Isenberg, E. J. (2006). The choice of public, private, or home schooling. New York: National Center for the Study of Privatization in Education.

Isenberg, E. J. (2007). What Have We Learned About Homeschooling? Peabody Journal of Education, 82(2–3), 387–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/01619560701312996

Johnson, M. (2024). Black Homeschooling: A Response to Racialized Educational Terrain. Journal of School Choice, 18(4), 572–585. https://doi.org/10.1080/15582159.2024.2422241

Kitchen, P. (1991). Socialization of home school children versus conventional school children. Home School Researcher, 7(3), 7–13.

Kunzman, R. (2010). Homeschooling and religious fundamentalism. International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 3(1), 17–28.

Kunzman, R., & Gaither, M. (2020). Homeschooling: An updated comprehensive survey of the research. Other Education: The Journal of Educational Alternatives, 9(1), 253–336.

Lapon, E. (2021). Homeschooling During COVID-19: Lessons Learned from a Year of Homeschool Education. Home School Researcher, 37(1).

Lips, D., & Feinberg, E. (2008). Homeschooling: A Growing Option in American Education. Heritage Foundation, 2122.

Lois, J. (2013). Home is where the school is: The logic of homeschooling and the emotional labor of mothering. NYU Press.

Lubienski, C., Puckett, T., & Brewer, T. J. (2013). Does Homeschooling “Work”? A Critique of the Empirical Claims and Agenda of Advocacy Organizations. Peabody Journal of Education, 88(3), 378–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/0161956X.2013.798516

Maranto, R. (2021). Between Elitism and Populism: A Case for Pluralism in Schooling and Homeschooling. Journal of School Choice, 15(1), 113–138.

Maranto, R., & Bell, D. A. (2018). Homeschooling in the 21st Century: Research and Prospects. Routledge.

Marks, D., & Welsch, D. M. (2019). Homeschooling Choice and Timing: An Examination of Socioeconomic and Policy Influences in Wisconsin. Journal of School Choice, 13(1), 33–57.

Mazama, A., & Musumunu, G. (2014). African Americans and homeschooling: Motivations, opportunities and challenges.

McCluskey, N. (n.d.). Private Schooling after a Year of COVID-19: How the Private Sector Has Fared and How to Keep It Healthy. Cato Institute, 914.

Medlin, R. G. (2006). Homeschooled Children’s Social Skills. Online Submission, 17(1), 1–8.

Medlin, R. G. (2013). Homeschooling and the question of socialization revisited. Peabody Journal of Education, 88(3), 284–297.

Monarrez, T., & Chingos, M. (2020). Can we measure school quality using publicly available data. Center on Education Data Policy.

Morgan, C. (2012). Home Schooled vs. Public Schooled. Unpublished Master’s Thesis, Northern Michigan University.

Murphy, J. (2012). Homeschooling in America: Capturing and Assessing the Movement. Corwin.

Neuman, A., & Guterman, O. (2017). Homeschooling Is Not Just About Education: Focuses of Meaning. Journal of School Choice, 11(1), 148–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/15582159.2016.1262231

Pensiero, N., Kelly, A., & Bokhove, C. (2020). Learning inequalities during the Covid-19 pandemic: How families cope with home-schooling. University of Southampton. https://doi.org/10.5258/SOTON/P0025

Qaqish, B. (2007). An Analysis of Homeschooled and Non-Homeschooled Students’ Performance on an ACT Mathematics Achievement Test. Home School Research, 17(2), 1–12.

Ray, B. D. (2000). Home Schooling for Individuals’ Gain and Society’s Common Good. Peabody Journal of Education, 75(1–2), 272–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/0161956X.2000.9681945

Ray, B. D. (2004). Homeschoolers on to College: What Research Shows Us. Journal of College Admission, 185, 5–11.

Ray, B. D. (2013). Homeschooling Associated with Beneficial Learner and Societal Outcomes but Educators Do Not Promote It. Peabody Journal of Education, 88(3), 324–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/0161956X.2013.798508

Ray, B. D. (2015). African American Homeschool Parents’ Motivations for Homeschooling and Their Black Children’s Academic Achievement. Journal of School Choice, 9(1), 71–96.

Ray, B. D. (2017). A systematic review of the empirical research on selected aspects of homeschooling as a school choice. Journal of School Choice, 11(4), 604–621. https://doi.org/10.1080/15582159.2017.1395638

Schneider, J. (2017). Beyond test scores: A better way to measure school quality. Harvard University Press.

Singer, J. (2021). Power to the People? Populism and the Politics of School Choice in the United States. Journal of School Choice, 15(1), 88–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/15582159.2020.1853993

Smith, G., & Watson, A. R. (2024). Estimating Homeschool Participation in the U.S. – What We Can Learn from the Household Pulse Survey. Journal of School Choice, 18(4), 501–517. https://doi.org/10.1080/15582159.2024.2422239

Stevens, M. (2009). Kingdom of children: Culture and controversy in the homeschooling movement. Princeton University Press.

Tilhou, R. (2020). Contemporary Homeschool Models and the Values and Beliefs of Home Educator Associations: A Systematic Review. Journal of School Choice, 14(1), 75–94.

Williams-Johnson, M., & Fields-Smith, C. (2022). Homeschooling among Black families as a form of parental involvement: A focus on parental role construction, efficacy, and emotions. Educational Psychologist, 57(4), 252–266. ¯