Home School Researcher Volume 39, No. 3, 2025, p. 1-11

Nancy Leech

Professor, School of Education & Human Development, University of Colorado Denver, Denver, Colorado, nancy.leech@ucdenver.edu

Miriam Howland Cummings

Ph.D. Student, School of Education and Human Development, University of Colorado Denver, Denver, Colorado miriam.cummings@ucdenver.edu

Sophie Gullett

Analyst, People Analytics, The New Teacher Project, Los Angeles, CA, sophie.gullett@tntp.org

Carolyn A. Haug

Senior Instructor, School of Education and Human Development, University of Colorado Denver, Denver, Colorado, carolyn.haug@ucdenver.edu

Abstract

More families have chosen to homeschool since the COVID-19 pandemic. Participants included 64 homeschooling parents and 661 teachers. This survey-based quantitative study utilized the Professional Quality of Life Scale to understand the level of compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress of homeschooling parents. Parents were recruited through social media platforms. Data from a previous study with in-service teachers was used as a comparison. Results indicate that longer term homeschooling parents feel satisfied with their work. Those new to homeschooling, especially when choosing to homeschool due to a pandemic, need support and awareness of the possibility of experiencing burnout.

Keywords: homeschooling; remote learning; COVID19 pandemic; ProQOL

Background

Professional quality of life is important for everyone, especially those in helping professions such as nurses, counselors, teachers, police officers, firefighters, etc. (Stamm, 2010). Professional quality of life has been defined as “the quality one feels in relation to their work as a helper” (Stamm, 2010, p. 8). Stamm (2010) delineates two underlying aspects to quality of life: the positive aspect is compassion satisfaction, and the negative is compassion fatigue (Stamm, 2010). The negative aspect of compassion fatigue is broken down even further to include burnout and secondary traumatic stress, which is defined as “a negative feeling driven by fear and work-related trauma” (Stamm, 2010, p. 8).

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID19) pandemic impacted professional quality of life across the world during 2020 (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020). The virus hit the United States during the spring of 2020, resulting in the closure of businesses, restaurants, events, and schools in an attempt to reduce the spread of the virus (Wynne, 2020). For students in P-12 schools, in-person learning shut down across the US during March of 2020 and parents’ home environments changed dramatically as a result of the pandemic. Many parents shifted from working outside of the home to working from home and had to juggle their own work responsibilities with the new responsibility of supporting their child’s learning (Durden, 2020).

In many places, in-person learning did not resume until the fall of 2020, at which point there was a mix of in-person, remote, and hybrid instruction across schools. Districts cycled between these learning methods as cases surged or lessened in their region (Lieberman, 2020). As a result of these constant changes, as well as other issues with how districts handled learning during a pandemic, many parents decided to take their students’ learning into their own hands (Green, 2020). These parents shifted to homeschooling rather than having their child do remote learning: they took much more responsibility for directly facilitating their children’s learning (Green, 2020). In this paper, homeschooling is defined as learning from a parent without assistance from a school. This differs from remote learning for students during the pandemic where students were learning at home with schooling being provided by a teacher at a school. Some reports have indicated that the number of parents choosing to homeschool their children doubled during the pandemic (Brenan, 2020; Prothero & Samuels, 2020). In general, these parents indicated an overall dissatisfaction with remote learning and a desire for a more consistent and high-quality education, which they hoped to provide through homeschooling (Brenan, 2020).

In most cases prior to the pandemic, families choose to homeschool as a result of their values and beliefs, not because they were forced to make this transition (Baker, 2019).

However, the pandemic impacted the dynamics of many families by altering their daily lives as well as the roles they held to support their family (Shen & Kruger, 2022). During the pandemic, many parents—most often mothers—had to give up employment to take on the daily childcare needs that schools had previously been meeting (Petts et al., 2020). Because of these new roles and the stresses of transitioning to remote learning, parents exhibited higher stress levels during the pandemic compared to non-parents (American Psychological Association, 2020).

Switching to remote learning required teachers to spend a great deal of time adapting their content to the remote setting, often without the necessary resources or guidance (Boltz et al, 2021). This was true for parents who chose to homeschool as well, with many of them starting from scratch to create their lessons (Petts et al., 2020). Existing homeschoolers didn’t face the same challenges when the pandemic began, but still lost access to learning resources such as libraries, museums, and other community learning resources (The Hunt Institute, 2021). Many of them also rely on homeschooling communities (Anthony, 2015), which may have become harder to connect with during the pandemic.

Benefits of Homeschooling

Homeschooling provides families with many opportunities to help their children, including spending more time together as a family, removing commute time, providing more flexibility in scheduling and traveling, and tailoring learning to the needs and values of the family and child (McFall, 2020). Families may also choose homeschooling to better provide accommodations for students’ health needs (Lois, 2013). This was a particularly important consideration for families during the pandemic, as in-person learning may have resumed before families felt safe sending their children back or before schools had plans in place to support students with specific health concerns (Brandenburg et al., 2020).

Homeschooling also supports parents in being more involved in their children’s lives and learning. Families who homeschool tend to be engaged with learning (Basham et al., 2007; Jolly et al., 2012) and concerned with the well-being of the children (Hannah, 2012). Homeschooling parents are able to make more decisions about what and how to teach their children (Kunzman & Gaither, 2020). With a range of different pedagogies for homeschooling, homeschooling can also differ greatly between families and by the age of the children (Burke & Cleaver, 2019). This can result in learning that is more tailored to their child’s unique needs and the values of their family (Kunzman & Gaither, 2020).

Challenges of Homeschooling

Unfortunately, there are drawbacks to homeschooling as well (Shen & Kruger, 2022). Burnout happens for homeschoolers and homeschooling families, especially for mothers who tend to be responsible for most of the homeschooling activities (Lois, 2010, 2013). Taking on the role of teacher and parent can be emotional and physically demanding and result in role strain (Boyle et al., 1995; Friedman, 2003). This strain is exacerbated if the homeschooling parent also works and must juggle a career in addition to teaching and parenting responsibilities (Green & Hoover-Dempsey, 2007).

Homeschooling parents also have to be more intentional about providing opportunities for their children to socialize with same-aged peers and make friends. Many families have found ways to combat this, such as creating learning communities (Anthony, 2015). Homeschooling parents have been able to provide many opportunities for socialization that result in strong relationships with friends and families and well-developed social skills (Medlin, 2013). However, this would likely be more difficult for parents who began homeschooling during the pandemic (Pozas, Letzel, & Schneider, 2021).

The Goal and Research Questions for the Current Study

The goal of the current study is to explore the experiences of parents schooling their children during the pandemic. It also seeks to understand how this experience may have been different for long-term homeschoolers versus other homeschooling parents as a result of the pandemic, as well as for teachers versus homeschooling parents. Three overarching research questions were explored in this study: (a) Do the data from the homeschooling parents and public school teachers similarly fit the models from Stamm (2010)?; (b) Is there a difference between long-term homeschoolers versus other homeschooling parents who started homeschooling during the pandemic on compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress?; and (c) Is there a difference between homeschoolers versus classroom teachers who were teaching remotely during the pandemic on compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress?

Method

This survey-based quantitative study is part of a larger series of studies regarding remote teaching and learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Approval for this study was granted by the authors’ university’s institutional review board (IRB).

Participants

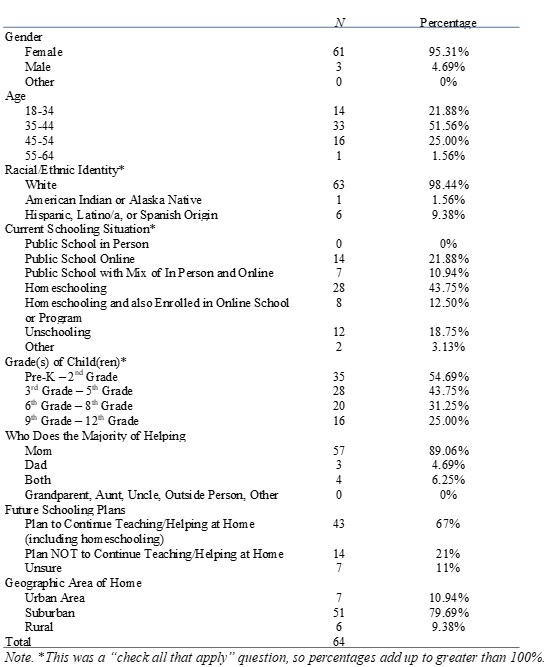

Participants were 64 homeschooling parents of school-aged children during the COVID-19 pandemic. While this is a somewhat small sample size, during a global pandemic which precipitated an unprecedented schooling situation, this sample size is still valuable in beginning to gain an understanding of parents’ experience during the unique time of COVID-19. Regarding the format of schooling their children had been receiving prior to COVID-19, 0 participants indicated public school in person, 14 public school online, 7 public school with a mix of in person and online instruction, 28 homeschooling, 8 homeschooling and also enrolled in an online school or program, 12 unschooling, and 2 participants indicated “other.” Participants had a range of experience in teaching, helping, or homeschooling children ranging from 0 years to 23 years, with a median of 4 years’ experience and mode of 1 year experience. On average, most participants were teaching/helping 2 children, as this was the mean, median, and mode. A total of 55% of participants had children in grades Pre-K through 2nd, 44% in grades 3rd-5th, 31% in grades 6th-8th, and 25% in grades 9-12. When asked who did the majority of the teaching/helping, 89% of participants indicated Mom, 4.7% indicated Dad, 6.3% indicated both, and 0% indicated grandparent, aunt, uncle, outside person, or other.

Of the 64 participants, 67% indicated that they planned to continue with teaching/helping their children at home (including homeschooling), while 21% indicated they did not plan to continue, and 11% were unsure. Fifty-four participants lived in a single specific state of the Western U.S., while 10 lived in other states around the U.S; 7 lived in urban areas, 51 in suburban areas, and 6 in rural areas. Participants were comprised of 95% females and 5% males, with 22% in the 18-34 age range, 52% in the 35-44 age range, 25% in the 45-54 age range, and 2% in the 55-64 age range. Finally, 98% of participants were White, 2% were American Indian or Alaska Native, and 10% were of Hispanic, Latina/o, or Spanish origin. See Table 1 for demographic information.

Table 1

Demographics

For the third research question, “Is there a difference between homeschoolers versus classroom teachers who were teaching remotely during the pandemic on compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress?” data from Leech et al. (2022) were used for comparison with the homeschool participants. Teacher participants included 661 respondents with an average tenure of teaching of 14 years (range = 0.75 – 41 years). Most of the teachers taught worked with pre-K through 2nd grade (28.7%), 3rd through 5th grade (30.4%), 6th through 8th grade (28.1%), and 9th through 12th grade (36.5%). Most (n = 655) of the teachers indicated their gender identity with 75.3% identified as female, 24.3% identified as male, and less than 1% identified as other. Ages of teachers included: 18-34 years old (24.3%), 35-44 years old (26.3%), 45-54 years old (29.6%), or 55-64 years old (17.7%), with the remaining 1.9% reporting being 65 or older. Most (96.1%) of the teacher participants identified as White, 1.5% identified as American Indian or Alaskan Native, 1.3% identified as Black or African American, and 0.9% identified as Asian. 9.2% of teachers reported that they were of Hispanic, Latinx or Spanish origin.

Procedure

After IRB approval was obtained, the following explanation of the study and the link to the survey was posted during September 2020 on one of the author’s social media accounts.

- How is school/homeschool going for you during COVID19?

- We would like to hear from you about your experiences teaching/helping your children with school this year. If you have a child in school, whether you are remote schooling, schooling in person, doing online school, or homeschooling, we want to hear from you!

- We are researchers from University of Colorado Denver and are interested in understanding what is working and what is not working with school this year!

The link to the survey was open for 18 days, and the opening statement of the survey was, “You are being asked to be in this research study because you are a parent helping your child with their schooling or homeschooling during the COVID-19 pandemic.” The survey was administered using the online tool RedCap (Harris et al., 2009) and took approximately 15 minutes to complete.

Instrumentation

The survey included three main sections: the Professional Quality of Life Scale (ProQOL5; Stamm, 2010), the EDUCAUSE DIY Survey Kit: Remote Work and Learning Experiences (EDUCAUSE, 2020), and demographic questions. The focus of this study was the ProQOL5. The ProQOL5 included 30 items (e.g., “I feel connected to others” and “I feel overwhelmed because my workload seems endless”) with Likert-type response options ranging from 1 (“Never”) to 5 (“Very Often”).

The stated purpose of the ProQOL5 is to assess people’s perceptions of their quality of life, and as stated in the manual (Stamm, 2010) is specifically focused on quality of life for helpers. Although the participants in this study were homeschooling parents and were not necessarily professionally involved in helping (e.g., participants were not necessarily paid to be teachers), each had taken on a helping and teaching role with relation to their child at home during the COVID-19 pandemic. The ProQOL5 conceptualizes the construct of quality of life with two factors: compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue. Compassion fatigue is then further divided into two subfactors, burnout and secondary traumatic stress.

Compassion satisfaction is defined as “the pleasure…derive[d] from being able to do your work well” (Stamm, 2010, p. 12). Compassion satisfaction is a construct associated with positive affect, whereas compassion fatigue (including both burnout and secondary traumatic stress) is associated with negative affect. Burnout is characterized by feeling ineffectual as though one’s efforts make no difference, finding it difficult to complete tasks, and a general feeling of hopelessness regarding the way one is helping others (Stamm, 2010). Secondary traumatic stress is defined as “work-related, secondary exposure to people who have experienced extremely or traumatically stressful events” (Stamm, 2010, p. 13). Further, Stamm (2010) goes on to explain that “the negative effects of [secondary traumatic stress] may include fear, sleep difficulties, intrusive images, or avoiding reminders of the person’s traumatic experiences” (p. 13).

Dimensionality of the ProQOL has been examined by other researchers (e.g., Heritage et al., 2018), but for the purpose of this study, dimensionality will be considered in a confirmatory manner as intended by its developers (Stamm, 2010), with compassion satisfaction as one factor and compassion fatigue as another factor with two subfactors, burnout and secondary traumatic stress. The ProQOL manual reports Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress as 0.88, 0.75, and 0.81, respectively (Stamm, 2010). For the sample in this study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were 0.96, 0.91, and 0.851, respectively.

Analysis

After data were collected using REDCap (Harris et al., 2009) the data were imported from REDCap to IBM SPSS version 29 and Amos version 29 for analysis. Analyses were conducted in multiple steps. First, in order to assess if the data fit the model purported by Stamm (2010) and utilized in companion research regarding teachers’ ProQOL results (Leech et al., 2022) a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted. Because the current study included a comparison of factor means from the companion study (Leech et al., 2022), it was important for the exact factor structure and item set to be utilized in the current study. For this reason, the factor structure presented in that study (Leech et al., 2022), which opted to conduct three separate CFAs – one for each subfactor – was replicated for this CFA.

Model fit was assessed using the chi-square test, the comparative fit index (CFI) and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). For the chi-square index, lower values indicate better model fit, but should not be considered in isolation as it tends to be a less reliable fit index because it is highly influenced by sample size. For CFI, Hu and Bentler

(1999) suggest that values of .9 and above may indicate good model fit. For RMSEA, Brown and Cudeck (1993) as well as MacCallum et al. (1996) suggest that values larger than .1 may indicate poor model fit, values between .08 and .10 may indicate mediocre model fit, values between ,05 and .08 may indicate acceptable model fit, and values below .05 may indicate good model fit. Full-information maximum likelihood estimation was employed to address missing data. The sample size was somewhat low as CFA models with two to four factors need approximately 100 cases (Loehlin, 1992). Having a small sample size would increase the likelihood of the models not fitting based on the chi-square index. Therefore, if the chi-square index is statistically significant for the current data, the number of cases appears to be adequate.

Next, in order to determine if there were differences in levels of compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary trauma stress between teachers and homeschooling parents, one-sample t tests were conducted. Means for these constructs for teachers were pulled from a companion study (Leech et al., 2022) to use as a comparison. Lastly, in order to determine if there were differences in compassion satisfaction, burnout, or secondary traumatic stress based on parents’ histories of homeschooling, independent sample t tests were conducted. Homeschooling parents were sorted into two groups: history of homeschooling (1.5+ years of homeschooling experience before the pandemic) or new to homeschooling (those that began homeschooling because of the pandemic). To decrease the Type I error from the six inferential statistics being conducted, the Bonferroni correction was computed and an alpha value of .008 was used, thus, a p value would need to be less than .008 to be considered statistically significant.

Results

Confirmatory Factor Analyses

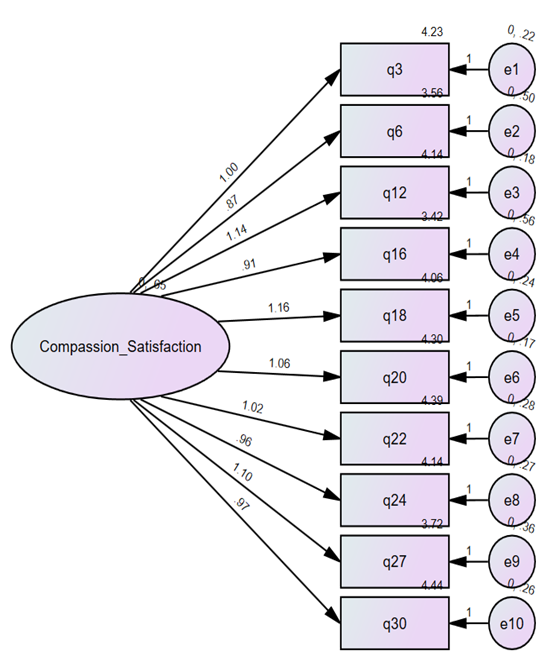

In order to be consistent with the factor structure and method presented in the companion study (Leech et al., 2025), from which teacher means were extracted and compared, three separate CFAs were conducted, one for each subfactor. For the Compassion Satisfaction factor, the data were an acceptable fit to the model (χ2 = 72.81, p < .001; CFI = .94; RMSEA = .13). Although the RMSEA value was a bit high, the CFI value was good, indicating a model fit acceptable for this study. Figure 1 presents all factor loadings which were statistically significant and strong, with standardized regression weights ranging from .70 to .91.

Figure 1

Confirmatory Factor Analysis for the Sub-Factor of Compassion Satisfaction

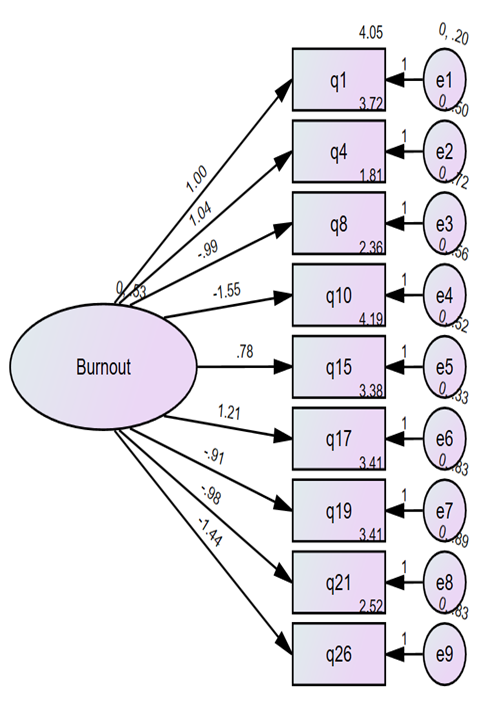

For the Burnout factor, the data demonstrated an acceptable fit to the model (χ2 = 73.47, p < .001; CFI = .85; RMSEA = .16). Although model fit ideally would have been better, due to the small sample size and relevance of the research topic, this model fit was deemed acceptable for this study. Figure 2 presents all factor loadings which were statistically significant and strong, with standardized regression weights ranging from .59 to .85.

Figure 2

Confirmatory Factor Analysis for the Sub-Factor of Burnout

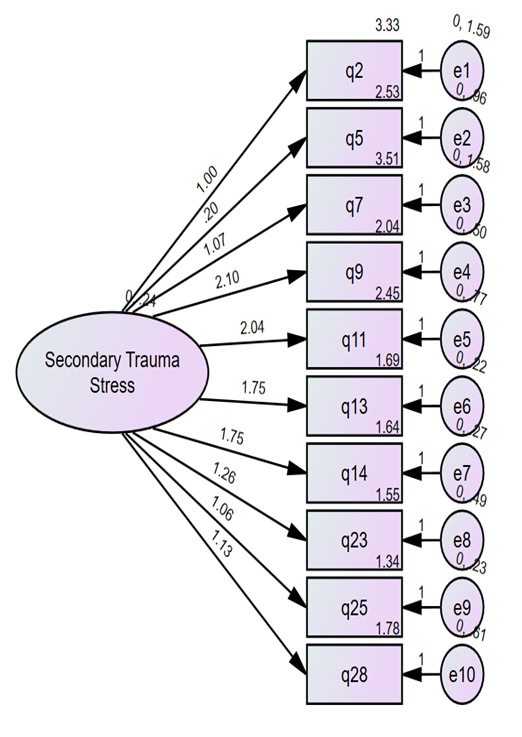

Finally, for the Secondary Trauma Stress factor, the data demonstrated an acceptable fit to the model (χ2 = 79.74, p < .001; CFI = .85; RMSEA = .14). Again, although model fit ideally would have been better, due to the small sample size and relevance of the research topic, this model fit was deemed acceptable for this study. All items demonstrated statistically significant and strong factor loadings except for one item, which was not statistically significant and had a weak standardized regression weight (.10). Although removing this item would have improved model fit, it was necessary to retain the item in order to compare the factor mean for homeschooling parents (in this study) with the factor mean for teachers (in a previous study; Leech et al., 2022). Because the previous study included this item in its Secondary Trauma Stress factor, the item needed to be retained in the current study so that a comparison could be made. Figure 3 presents the factor loadings; the items loaded with standardized regression weights ranging from .36 to .88.

Figure 3

Confirmatory Factor Analysis for the Sub-Factor of Secondary Trauma Stress

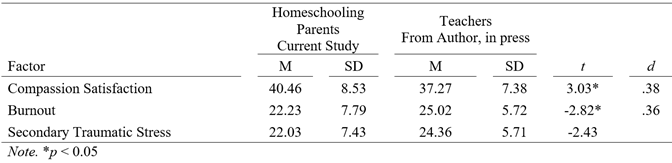

Differences between Homeschooling Parents and Teachers

One sample t tests were conducted to determine whether there was a difference in subscale scores on the ProQOL between homeschooling parents and teachers. Teacher means were pulled from previous research to be used as comparison data (Leech et al., 2022). Table 2 includes the one sample t test results which are a comparison of the means for homeschooling parents and teachers. There was a statistically significant difference between teachers (M = 37.21, SD = 7.38) and homeschooling parents (M = 40.46, SD = 8.53) on compassion satisfaction, t(62) = 3.03, p = .004, d = .38. The effect size of Cohen’s d is considered small to typical (Morgan et al., 2020). Homeschooling parents had statistically significantly higher compassion satisfaction, suggesting that homeschooling parents have higher compassion for their children while teaching their children at home than teachers do while teaching their students remotely. There was a statistically significant difference between teachers (M = 25.02 , SD = 5.72) and homeschooling parents (M = 22.23, SD = 7.79) on burnout, t(61) = -2.82, p = .006, d = .36. The effect size of Cohen’s d is considered small to typical (Morgan et al., 2020). Teachers had statistically significantly higher burnout, suggesting that they are experiencing higher burnout while remote teaching than homeschooling parents. There was not a statistically significant difference between teachers (M = 24.36 , SD = 5.71) and homeschooling parents (M = 22.03, SD = 7.43) on secondary traumatic stress. While teachers had higher secondary traumatic stress, indicating that they may be experiencing more traumatic stress while remote teaching than homeschooling parents, the difference was not statistically significant.

Table 2

Means Comparison, Homeschooling Parents. v. Teachers: One-Sample t tests

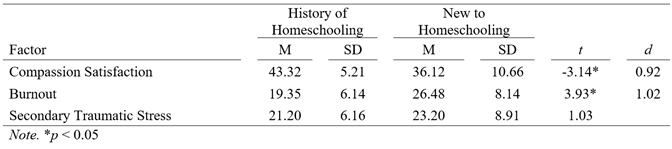

Differences between Homeschooling Parents

Table 3 presents the independent sample t tests conducted to determine if there were differences in compassion satisfaction, burnout, or secondary traumatic stress based on parents’ histories of homeschooling. Homeschooling parents were sorted into two groups: history of homeschooling (1.5+ years of homeschooling experience before the pandemic) or new to homeschooling (those that began homeschooling because of the pandemic). There was a statistically significant difference between parents with a history of homeschooling (M = 43.32 , SD = 5.21) and parents new to homeschooling (M = 36.12, SD = 10.66) on compassion satisfaction, t(31.62) = -3.14, p = .004, d = .92. The effect size of Cohen’s d is considered larger than typical (Morgan et al., 2020). Parents with a history of homeschooling had statistically significantly higher compassion satisfaction, indicating that they may derive more satisfaction from homeschooling their children than parents who are new to

homeschooling. There was a statistically significant difference between parents with a history of homeschooling (M = 19.35 , SD = 6.14) and parents new to homeschooling (M = 26.48, SD = 8.14) on burnout, t(60) = 3.93, p < .001, d = 1.02. The effect size of Cohen’s d is considered much larger than typical (Morgan et al., 2020). Parents with a history of homeschooling had statistically lower burnout, indicating that they are experiencing less burnout from homeschooling than parents who are new to homeschooling. There was not a statistically significant difference between parents with a history of homeschooling (M = 21.2 , SD = 6.16) and parents new to homeschooling (M = 23.2, SD = 8.91) on secondary traumatic stress. While parents with a history of homeschooling had lower average secondary traumatic stress than parents new to homeschooling, the difference was not statistically significant. This difference was smaller than for other subscales, so the group sizes may not have been larger enough to provide the power to detect a difference.

Table 3

Means Comparison, History of Homeschooling: Independent-Samples t tests

Discussion

This study was conducted to better understand homeschoolers, both long-term homeschoolers and those new to homeschooling, during a pandemic on compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress. We were also interested in better understanding the similarities and differences between homeschooling parents and teachers on these constructs. Specifically, this study hoped to answer the following research questions: (a) Do the data from the homeschooling parents and public school teachers similarly fit the models from Stamm (2010)?; (b) Is there a difference between long-term homeschoolers versus other parents who started homeschooling during the pandemic on compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress?; and (c) Is there a difference between homeschoolers versus classroom teachers who were teaching remoting during the pandemic on compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress? Understanding people who teach, both in schools as teachers and in homes as homeschoolers, will provide information for where support is needed to address the mental health of the educators, regardless of context.

In this study, two types of mental health issues were investigated as measured by Stamm (2010): compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue. Compassion satisfaction is defined as the ability to find pleasure from doing work well. Compassion fatigue is made up of burnout, defined as feeling ineffectual or hopeless as a result of work, and secondary traumatic stress, defined as a secondary exposure to people who have experienced a stressful event. In the current study, homeschooling parents reported higher compassion satisfaction than teachers. Homeschooling parents are aligned and connected with their children, and they do the work of homeschooling out of love and wanting their child to succeed (McCabe et al., 2021). Thus, the finding that homeschooling parents find pleasure from doing work well, is not surprising and aligns with the literature (McCabe et al., 2021).

The second result from the current study was that teachers reported higher levels of burnout than homeschooling parents. Teachers have been known to experience burnout (García-Carmona et al., 2019; Pyhältö et al., 2021) due to a multitude of reasons such as workload (Brewer & Shapard 2004), years of teaching experience (van Droogenbroeck et al. 2014), not feeling appreciated (Gavish & Friedman, 2010), and extensive and prolonged work-related stress (Foley & Murphy, 2015). Homeschooling parents also experience burnout (Lois, 2010, 2013) as homeschooling can take parents many hours of teaching, providing learning opportunities, fieldtrips, and planning, although to a lesser extent than teachers.

When comparing long-term homeschooling parents to new to homeschooling parents, long-term homeschooling parents had higher compassion satisfaction and lower burnout than new to homeschooling parents. These findings were not unexpected as most homeschooling parents view schooling their children as a gift, not a burden (McCabe et al., 2021), yet new to homeschooling parents during the pandemic were most likely frantically learning how to homeschool (Gallagher & Egger, 2020).

There was not a statistically significant difference between the three groups on secondary traumatic stress. Yet, interestingly, those with a history of homeschooling had the lowest secondary traumatic stress (M = 21.20) and teachers had the highest amount of secondary traumatic stress (M = 24.36). This difference, although not statistically significant, could be from less overall life changes occurring for those with a history of homeschooling as homeschoolers were already doing school at home and thus had less change in their routine when the pandemic happened (The Hunt Institute, 2021).

Implications

Findings from this study have implications for teachers, schools, districts, and parents. Teaching can be challenging when done under unfamiliar circumstances, such as the sudden remote teaching requirements due to the pandemic, even for those who have been prepared as professional teachers. It can be associated with burnout, stress, and job dissatisfaction. The pandemic has exacerbated an already difficult job. This has implications for schools and districts in terms of faculty mental health services and teacher retention efforts that may be needed. As well, these findings have implications for parents entering homeschooling, a situation that may be harder than they anticipate and could lead to burnout. It suggests that new homeschooling parents may want to find support systems. Finally, there are implications for schools welcoming students who were formerly homeschooled. This study suggests that it is important for schools to understand that previously-homeschooled students may have quite different profiles and should receive careful assessment of both academic and social needs.

Limitations

There are limitations to the current study. The homeschooling parent group was relatively small. Past research has found homeschoolers tend to avoid participating in research (Valiente et al., 2022), so this low sample size was not unexpected. Furthermore, the data were self-reported survey data. Finally, there may be other confounding variables that were not considered in the study that impacted the homeschooling parents and teachers.

Conclusions

Understanding homeschooling parents and their role as a teacher is important as more families are choosing to homeschool (Smith & Campbell, 2023). To have successful homeschooling experiences, learning how to support homeschooling families regarding the mental health of the parents is important to consider. It is also important to understand that some students who were homeschooled during the pandemic were being taught by brand new homeschool parents and may have had different experiences than those of peers with long-term homeschooling parents. Hopefully, this study creates discussion about outcomes and needs of students experiencing homeschooling during the pandemic and related issues.

References

American Psychological Association. (2020). Stress in the time of COVID-19, 1. https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/stress/2020/stress-in-america-covid.pdf

Anthony, K. V. (2015). Educational cooperatives and the changing nature of home education: Finding balance between autonomy, support, and accountability. Journal of Unschooling and Alternative Learning, 9(18), 36-63.

Baker, E. E. (2019). Motherhood, homeschooling, and mental health. Sociology Compass, 13(9), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12725

Basham, P., Merrifield, J., & Hepburn, C. R. (2007). Homeschooling: From the extreme to the mainstream (2nd ed.). Frasier Institute.

Boltz, L. O., Yadav, A., Dillman, B., & Robertson, C. (2021). Transitioning to remote learning: Lessons from supporting K-12 teachers through a MOOC. British Journal of Educational Technology, 52(4), 1377-1393. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13075

Boyle, G. J., Borg, M. G., Falzon, J. M., & Baglioni, A. J. (1995). A structural model of the dimensions of teacher stress. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 65(1), 49-67. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.1995.tb01130.x

Brandenburg, J. E., Holman, L. K., Apkon, S. D., Houtrow, A. J., Rinaldi, R., & Sholas, M. G. (2020). School reopening during COVID-19 pandemic: Considering students with disabilities. Journal of Pediatric Rehabilitation Medicine, 13(3), 425-431. https://doi.org/10.3233/PRM-200789

Brenan, M. (2020, August 25). K-12 parents’ satisfaction with child’s education slips. Gallup.

Brewer, E. W., & Shapard, L. (2004). Employee burnout: a meta-analysis of the relationship between age or years of experience. Human Resource Development Review, 3(2), 102–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484304263335

Burke, K., & Cleaver, D. (2019). The art of home education: An investigation into the impact of context on arts teaching and learning in home education. Cambridge Journal of Education, 49(6), 771-788. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2019.1609416

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, April 27). Coronavirus Disease 2019. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/global-covid-19/index.html

Durden, W. G. (2020, April 8). Turning the tide on online learning. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/views/2020/04/08/online-learning-can-only-be-viable-if-it -offers-certain-connection-points

EDUCAUSE. (2020). EDUCAUSE DIY Survey Kit: Remote Work and Learning Experiences. https://er.educause.edu/blogs/2020/4/educause-diy-survey-kit-remote-work-and-learning-experiences

Foley, C., & Murphy, M. (2015). Burnout in Irish teachers: investigating the role of individual differences, work environment and coping factors. Teaching and Teacher Education, 50, 46–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2015.05.001

Friedman, I. A. (2003). Self-efficacy and burnout in teaching: The importance of interpersonal-relations efficacy. Social Psychology of Education, 6(3), 191-215. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024723124467

Gallagher, R., & Egger, H. L. (2020). School’s out: A parents’ guide for meeting the challenge during the COVID-19 pandemic. NYU Langone Health. https://nyulangone.org/news/schools-out-parents-guide-meeting-challenge-during-covid-19-pandemic

García-Carmona, M., Marín, M. D., Aguayo, R. (2019).Burnout syndrome in secondary school teachers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Social Psychology of Education, 22(1), 189-208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-018-9471-9

Gavish, B., Friedman, I. A. (2010). Novice teachers’ experience of teaching: A dynamic aspect of burnout. Social Psychology of Education, 13, 141–167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-009-9108-0

Green, C. L., & Hoover-Dempsey, K. V. (2007). Why do parents homeschool? A systematic examination of parental involvement. Education and Urban Society, 39(2), 264–285. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013124506294862

Green, E. (2020, September 13). The pandemic has parents fleeing from schools – maybe forever. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2020/09/homschooling-boom-pandemic/616303/

Hanna, L. G. (2012). Homeschooling education: Longitudinal study of methods, materials, and curricula. Education and Urban Society, 44, 609-631

Harris, P. A., Taylor, R., Thielke, R., Payne, J., Gonzalez, N., & Conde, J. G. (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support, Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 42(2), 377-381. https://doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010

Heritage, B., Reese, C., & Hegney, D. (2018). The ProQOL-21: A revised version of the Professional Quality of Life (ProQOL) scale based on Rasch analysis. PLoS One, 13(2), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0193478

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1-55.

Jolly, J. L., Matthews, M. S., & Nester, J. (2013). Homeschooling the gifted: A parent’s perspective. Gifted Child Quarterly, 57, 121-134.

Kunzman, R., & Gaither, M. (2020). Homeschooling: An updated comprehensive survey of the research. Other Education: The Journal of Educational Alternatives, 9(1), 253-336.

Leech, N. L., Benzel, E., Gullett, S., & Haug, C. A. (2022). Teachers’ perceptions of work life during the pandemic of COVID 19: Validating the use of Professional Quality of Life Scale. International Journal of Multiple Research Approaches, 14(2), 55-72.

Leech, N. L., Gullett, S., Howland Cummings, M., & Haug, C. A. (2025). Schooling during COVID19: School at home, school at school, and school online [Manuscript in preparation]. School of Education and Human Development, University of Colorado Denver.

Lieberman, M. (2020, November 11). How hybrid learning is (and is not) working during COVID-19: 6 case studies. Education Week. https://www.edweek.org/leadership/how-hybrid-learning-is-and-is-not-working-during-covid-19-6-case-studies/2020/11

Loehlin, J. C. (1992). Latent variable models: An introduction to factor, path, and structural analysis (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Lois, J. (2010). The temporal emotion work of motherhood: Homeschoolers’ strategies for managing time shortage. Gender & Society, 24(4), 421-446.

Lois. J. (2013). Home is where the school is: The logic of homeschooling and the emotional labor of mothering. New York University Press.

MacCallum, R. C., Browne, M. W., & Sugawara, H. M. (1996). Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods, 1(2), 130. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.1.2.130

McCabe, M., Beláňová, A., Machovcová, K. (2021). The gift of homeschooling: Adult homeschool graduates and their parents conceptualize homeschooling in North Carolina. Journal of Pedagogy, 1, 119-140. https://doi.org/10.2478/jped-2021-0006

McFall, K. (2020). Why American parents choose homeschooling. Filoteknos, 10, 455-469.

Medlin, R. G. (2013). Homeschooling and the question of socialization revisited. Peabody Journal of Education, 88(3), 284-297.

Petts, R. J., Carlson, D. L., & Pepin, J. R. (2020). A gendered pandemic: Childcare, homeschooling, and parents’ employment during COVID-19. Gender, Work, & Organization, 28(2), 515-534. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/gwkzx

Pozas, M., Letzel, V., & Schneider, C. (2021). ‘Homeschooling in times of corona’: Exploring Mexican and German primary school students’ and parents’ chances and challenges during homeschooling. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 36(1), 35-50.

Prothero, A., & Samuels, C. A. (2020, November 9). Home schooling is way up with COVID-19. Will it last? EducationWeek. https://www.edweek.org/policy-politics/home-schooling-is-way-up-with-covid-19-will-it-last/2020/11

Pyhältö, K., Pietarinen, J., Haverinen, K., Tikkanen, L., & Soini, T. (2021). Teacher burnout profiles and proactive strategies. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 36, 219–242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-020-00465-6

Shen, J., & Kruger, M. (2022, January). COVID-19 and parental burnout levels. Applied Psychology Opus.

Smith, A. G., & Campbell, J. (2023). Homeschooling is on the rise, even as the pandemic recedes. Reason Foundation. https://reason.org/commentary/homeschooling-is-on-the-rise-even-as-the-pandemic-recedes/

Stamm, B. H. (2010). The concise ProQOL manual (2nd ed.). ProQOL.org

The Hunt Institute. (2021, April 30). Impact of COVID-19 on public libraries. https://hunt-institute.org/resources/2021/04/impact-of-covid-19-on-public-libraries/

Valiente, C., Spinrad, T. L., Ray, B. D., Eisenberg, N., & Ruof, A. (2022) Homeschooling: What do we know and what do we need to learn? Child Development Perspectives, 16, 48-53. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12441

Van Droogenbroeck, F., Spruyt, B., & Vanroelen, C. (2014). Burnout among senior teachers: Investigating the role of workload and interpersonal relationships at work. Teaching and Teacher Education, 43, 99–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2014.07.00

Wynne, S. K. (2020, March 12). Coronavirus closures: Walt Disney World, Universal Orlando Resort shutting down. Tampa Bay Times. tampabay.com/news/health/2020/03/12/coronavirus-disney-world-is-still-open-despite-crowd-warnings/¯