Home School Researcher Volume 39, No. 2, 2025, p. 1-8

Marta Giménez-Dasí

Faculty of Psychology, Complutense University of Madrid, Madrid, Spain, magdasi@ucm.es

Laura Quintanilla

Faculty of Psychology, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia, Madrid, Spain, lquintanilla@psi.uned.es

Renata Sarmento-Henrique

Department of Health Sciences, Nursing and Public Health Psychology, Saint Louis University – Madrid, renatalenise.sarmento@slu.edu

Abstract

This study examines the socioemotional well-being of a sample of Spanish homeschooled children and compares them with a sample of Spanish children attending a public school. 159 children aged 8-11 and their parents participated in the study. 75 children attended school and 84 were homeschooled. Parents and children separately completed different scales of the SENA questionnaire related to socioemotional well-being. Self-reported results showed significantly lower levels of Depression and Somatic complaints in homeschooled children compared to schooled children. No significant differences were found in other self-reported scales. Parents’ results indicated significantly lower levels of Depression, Attention problems, and Willingness to study in homeschooled children compared to schooled children. No significant differences were found in other hetero-reported scales. Differences were found based on gender. When comparing within each group, these differences remained significant only in the schooled children. These results provide insights into the socioemotional well-being of a previously unknown group of children in Spain and enable reflection on the possible effect of educational policies on child development.

Keywords: Home School; Socioemotional Well-being; Primary Education; Education Policies

The number of families who homeschool their children has increased significantly in recent decades. In the United States, the country where most families in this situation are found and where most research on this topic has been conducted, the number is estimated to have risen from 275,000 in 1990 to 1.7 million children in 2016 (McQuiggan et al., 2017). In recent years, the COVID-19 pandemic has led to a record number of children being homeschooled: 3.7 million children in the United States (Ray, 2022). Although this number has decreased over the past year (3.1 million children), approximately 3% of school-aged children in the United States are currently homeschooled (Ray, 2022).

The situation of these families varies greatly depending on the country of residence. In the United States and Canada, the countries where more families homeschool their children, homeschooling is legal. In Europe, the situation varies from being legal with no government regulation, as in the United Kingdom, to being prohibited, as in Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, Bulgaria, and Spain. Most European countries recognize homeschooling as a legal right. In some cases, they are governed by rather lax regulations (Austria, France, Belgium) and in others they are quite restrictive (Italy, Norway, Portugal) (Blok et al., 2017).

These differences in regulation reveal the lack of consensus on the benefits or harms of homeschooling. Previous studies and reviews indicate that there are two important issues that make a clear answer difficult: ideological issues and methodological issues (Kunzman & Gaither, 2020; Valiente et al., 2022). Most of the research conducted to show the effects of homeschooling has been done by the National Home Education Research Institute, an organisation that clearly advocates for homeschooling in the United States (Kunzman & Gaither, 2020). The conclusions of these investigations may be influenced by the authors’ personal interests, whether in support or opposition of homeschooling, suggesting a potential bias in their findings. In the United States, a significant proportion of families who choose to homeschool do so for ideological reasons, including religious education (Murphy, 2014). The 2016 National Survey on Home Education carried out in the United States, showed that families choose to homeschool for a variety of complex reasons, including religious or moral concern, dissatisfaction with the school environment, or deficiencies to address children’s special educational needs (Kunzman & Gaither, 2020; McQuiggan et al., 2017). One interesting finding that some authors have found is that many parents who homeschool their children have had bad experiences at school during their childhood, which contributed to a negative perception of the school context (Arai, 2000; Neuman, 2019; Wyatt, 2008).

The methodological problems found in these studies have also been pointed out by many authors (Kunzman & Gaither, 2020; Murphy, 2014; Valiente et al., 2022, among others). On the one hand, the samples are usually convenience samples and are not representative. On the other hand, many studies do not consider variables that could explain some of the differences, such as socioeconomic status, parental involvement, the starting time and years of homeschooling or specific contexts of children’ social relationships. Finally, most studies only use parents as informants. It would be desirable to include multi-informant measures obtained from other significant adults, the children themselves, and possible peers in the socialization contexts.

Social and emotional adjustment in homeschooled children

Previous studies that have evaluated the social and emotional adjustment of homeschooled children suffer from the just mentioned ideological and methodological problems, and therefore, it is difficult to draw clear conclusions. The issue of social and emotional adjustment is closely associated with socialization, which is a key issue in homeschooling. Socioemotional adjustment refers to a person’s ability to manage their emotions and establish healthy relationships with others. It involves the development of skills such as empathy, effective communication, and emotional regulation. This type of adjustment is fundamental for personal and social well-being, as it allows individuals to adapt to different situations, resolve conflicts, and maintain emotional balance in their lives (Denham, 2023). The homeschooling advocates appeal to the authoritarian and competitive environment of the educational system, the potential situations of peer mistreatment and/or discrimination as variables of the school context that may be detrimental to children’s social development (Dalaimo, 1996; Farris & Woodfrud, 2000; Medlin, 2000; Meighan, 1995; Murphy, 2014; Taylor, 1986). Detractors of homeschooling consider that the school context is critical in learning social norms, values, and social interaction skills, and that reducing it to the family context can lead to isolation and poor social and emotional development (Farris & Woodfrud, 2000; Medlin, 2000; Murphy, 2014; Romanowsky, 2001; Shyers, 1992).

Studies carried out almost exclusively in the United States seem to indicate that homeschooled children do not have difficulties building self-esteem, have better social skills (Murphy, 2014; Ray, 2017), develop a positive feeling of independence and self-determination (Knowles & Muchmore, 1995), exhibit good leadership skills (Sutton & Galloway, 2000) and have fewer behaviour problems (Haugen, 2004). However, a study conducted with a randomized sample in Canada in religious homeschooling contexts found that as homeschooled children became adults, they had less clarity about life goals, less effectiveness in dealing with life problems, and higher divorce rates compared to adults who had attended school (Pennings et al. 2012).

However, as Guterman and Neuman (2017) point out, most of these studies have three characteristics: 1) they have been carried out with adults who were homeschooled as children; 2) they assess children’s social activity only quantitatively; and 3) they do not compare the results of homeschooled children with children enrolled in schools matched on certain variables, such as age and socioeconomic level. Thus, the real impact of home school on children’s emotional and social development cannot be evaluated from these previous studies. To try to overcome these limitations, Guterman and Neuman (2017a) compared the levels of depression, internalizing and externalizing problems, and attachment security of a sample of 65 Israeli children aged 6 to 12 years who were homeschooled for at least 3 years with a group of 36 school children comparable in age and socioeconomic level. Results showed no significant differences in attachment security or internalizing problems. However, homeschooled children had significantly lower levels of depression and externalizing problems (this last difference was only found in the 9-to 12-year-old group). Subsequent analyses with the same population showed a negative and significant correlation between the number of encounters with other homeschooled children and levels of internalizing and externalizing problems and, surprisingly, a positive and significant correlation between the number of encounters with school children and levels of internalizing problems in the group of younger children (6-8 years) (Guterman & Neuman, 2017b). To our knowledge, Guterman and Neuman’s studies are the only ones conducted to date to evaluate the impact of home school on variables related to the social and emotional adjustment of children, using a matched group of schoolchildren to establish comparisons.

In line with Guterman and Neuman’s studies, the objective of this article is to explore the social and emotional well-being of a sample of Spanish homeschooled children and compare it with a sample of schooled children. Since there are no previous studies with these populations in Spain, this is an exploratory study. In Spain, school attendance is compulsory between the ages of 6 and 16 and failure to comply with this requirement can result in serious sanctions for parents. There are an estimated 2,000 Spanish families that are homeschooled. Since there are no official figures and these families are at risk of being sanctioned, this study works with the so-called hidden sample. It is also not known what kind of socialization experiences these children have, what their academic results are, what their development is like, or how they integrate into society when they finish their schooling period at home. To our knowledge, except for two studies on the characteristics of families (Goiria, 2008) and the history of home school in Spain (Cabo, 2012), there are no studies in Spain that evaluate the psychological state of children who are homeschooled.

The present study

This is an exploratory study aimed to study the socioemotional well-being of a sample of homeschooled children in Spain and compare it with a sample of children attending public schools. We evaluated children aged 8 to 11 years through self-report scales and hetero-report scales completed by families. Scales were related to children’s socialization, emotional regulation, mood and academic performance. Although this study cannot address some of the limitations of previous studies (i.e, convenience sample and lack of information of potential explanatory variables), it might contribute to the advancement of knowledge in three ways: it assesses socioemotional well-being including measures from the children themselves, it is conducted with a sample of participants from a different cultural context, and it investigates the possible effect of an illegal educational situation on socioemotional development.

Method

Participants

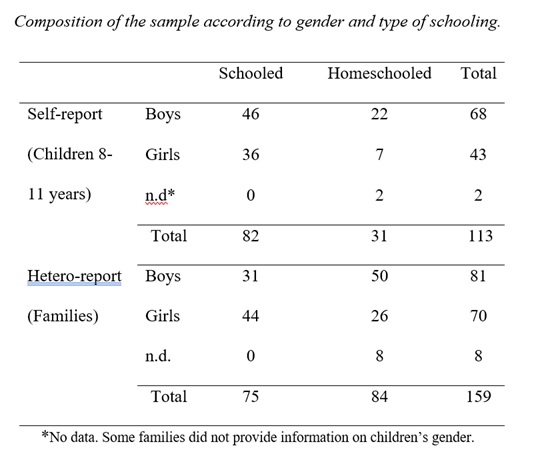

The participants were 159 children aged 8 to 11 years and their parents. 75 children attended public schools (Mage = 9.32, SD = .121) and 84 children were homeschooled (Mage = 8.09, SD = .285). The school that the children attended was located on the northwest outskirts of Madrid, and the families belonged to medium socioeconomic levels. We do not have any data on the place of residence or socioeconomic level of the 84 families who homeschool their children. Many of these families used pseudonyms and none wanted to be identified. However, at our request and in order to be able to compare with the schooled children, the association that gave us access to the sample chose middle-class families for the study. Table 1 shows the composition of the sample by gender and type of schooling.

Table 1

Instruments

The Child and Adolescent Assessment System Questionnaire (Sistema de Evaluación de Niños y Adolescentes – SENA, Fernández-Pinto et al., 2015), scaled for the Spanish population in its self-report and hetero-report version, was used. This questionnaire allows a broad exploration of child psychological adjustment, covering ages from 3 to 18 years. The test is divided into different scales that evaluate several aspects of child behaviour. To compare socioemotional well-being depending on the type of schooling we chose the scales related to adjustment and socioemotional skills.

For the self-report, in the version for 8-years-olds, the Depression (α=.87), Problems with Peers (α=.82), Family Problems (α=.55), Problems at School (α=.71), Interaction and Social Behaviour (α=.83), and Somatic Complaints (α=.81) scales were selected. Some items on the Problems with Peers and Problems at School scales had to be adapted to the context of homeschooled children. For example, the item “They insult me at school” from the Problems with Peers scale was adapted for homeschooled to “Other children insult me.” Similarly, in the Problems at School scale, the item “School is silly” was changed to “Studying is silly” for the homeschooled children. The rest of the scales did not need to be adapted since the statements of the items were adequate for the context of homeschooling (i.e. Depression: “I think my life has no meaning”; Family Problems: “My family supports me in the things that I do”; Interaction and Social Behaviour: “I make new friends easily” and Somatic Complaints: “I feel tired”).

For the hetero-report answered by the parents, the scales Depression (α=.85), Emotional Regulation (α=.84), Willingness to Study (α=.68), Attentional Problems (α=.91), Hyperactivity (α=.82) and Challenging Behaviour (α=.67) were chosen. In this case, it was not necessary to adapt the items of any scale since they were all applicable to the homeschooled context (i.e. Emotional Regulation: “Her/His emotional reactions are unpredictable”, Attentional Problems: “She/He finds it difficult to pay attention to what she/he is doing”; Hyperactivity: “He/She is impatient”; Challenging Behaviour: “He/She refuses to do the things I ask him to do”; Depression: “He/She seems discouraged”; Willingness to Study: “He/She thinks that studying is useless”). The instrument is scored on a Likert scale where 1 means “Never or almost never,” 2 “Rarely,” 3 “Sometimes,” 4 “Very often” and 5 “Always or almost always”. For the authors of the test, scores of 3 and above are indicative of problems. Thus, on most scales, high scores are indicative of problems or maladjustments. However, due to the wording of the items, in two of them, the high scores are interpreted positively. This is the case of the Interaction and Social Behaviour scale in the self-report measure and the Willingness to Study scale in the hetero-report.

Procedure

The present study is part of a broader investigation carried out by this research group at the school. The educational centre and families were informed about the objectives of the study and all the participants provided voluntary consent. Access to the sample of homeschooled children was obtained through an association using a “snowball” sampling technique. Both the association and the families that participated in the study, were informed of the objectives, and signed the consent to participate voluntarily. This research has been approved by the Deontological Committee of the Faculty of Psychology of the Complutense University of Madrid.

The SENA questionnaire was adapted to an online format using Google Forms to facilitate its accessibility. Both children and families completed the questionnaires online. The questionnaires were completed at the educational centre in the case of school students, supported by research team members, and at home in the case of the homeschooled children. The parents of the homeschooled children were told that they could only help them if they had difficulty with item comprehension. Parents agreed and were committed not to influence the children’s responses in any way.

Data Analyses

Data were analysed using SPSS version 25. Initially, the normality of the data was analysed with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov (K-S) test, applying a simulation of 1000 samples with 95% confidence. As the distribution of the sample data was not adjusted for normality in either the self-report or hetero-report (all p < .01), the mean differences between the two groups (schooled and homeschooled) were analysed with a non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test. Next, gender differences were also analysed using the Mann-Whitney U test.

Results

Self-report differences in socioemotional well-being

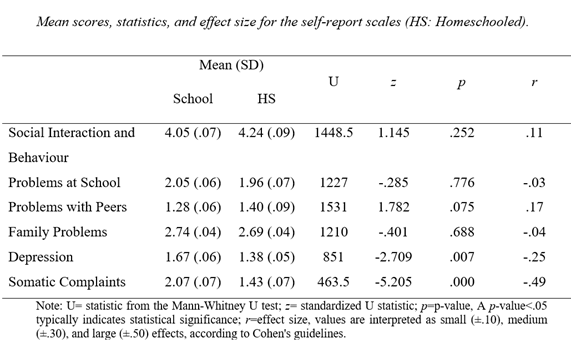

The self-report results for both groups -schooled children and homeschooled children – are presented in Table 2. The results of the Mann Whitney U test showed significant differences in two scales of the SENA test: Depression (p = .007) and Somatic Complaints (p < .001) scales. In both cases, the homeschooled children scored lower than the schooled children. As can be seen in Table 2, the other scales were not significant. The statistical indicators and effect size for each of the scales are included in Table 2. Following Cohen’s guidelines (Sulivan & Fein, 2012), the effect size is small in all cases except for the Somatic Complaints scale, where it can be considered medium (greater than .3).

Table 2

Hetero-report differences in socioemotional well-being

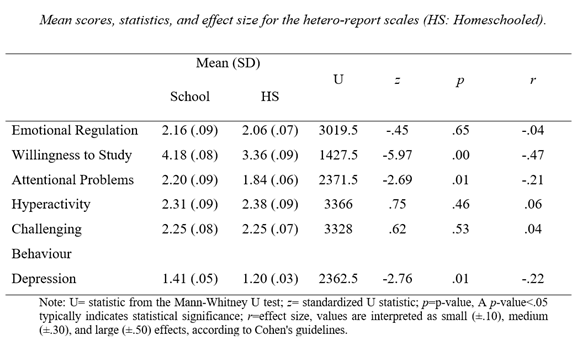

The mean scores of the hetero-report scales are presented in Table 3. As can be seen, there were significant differences in the Attentional Problems and Depression scales with a small effect size (less than .3), and in the Willingness to Study scale with a medium effect size (greater than .3). Homeschooled children scored lower than schooled children for the three scales.

Table 3

Gender differences

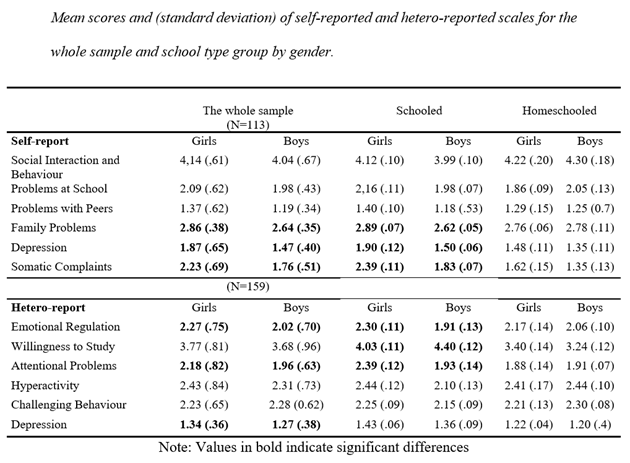

In the preliminary analysis, gender differences were found across the sample. Scores obtained for both genders in the different scales of the self-report and hetero-report questionnaires are presented in Table 4.

Self-report. Significant gender differences were found on whole sample (N=113, see Table 4) on Family Problems (U=1898, z=2.697, p=.0.01, r=.25), which had a small effect size (less than .3), as well as on Depression (U=2038, z=3.49, p=00, r=.33) and Somatic Complaints (U=2161, z=4.24, p=.00, r=.40), both of which exhibited medium effect sizes (greater than .3). In all 3 scales, girls scored higher than boys. When focusing on the gender differences for each group, significant differences were only observed in the schooled children (N = 82) on the Family Problems scale (U=1099, z=2.58, p=.01, r=.28.), with a low effect size (less than .3), as well as on Depression (U=1124.5, z=2.78, p=.01, r=.31) and Somatic complaints (U=1231, z=3.78, p=.0, r=.41.), both with medium effect sizes. Again, girls presented higher scores than boys in all three scales. No significant differences were observed based on gender for homeschooled children.

Hetero-report. Parents rated girls significantly higher than boys considering the entire sample (N=159, See Table 4) on Emotional Regulation (U=3546, z=1.97, p=.046, r=0.16), Attentional problems (U=3553, z=1.99, p=.046, r=0.16) and Depression (U=3565, z=2.07, p=.039, r=0.17) scales, all with small effect sizes (less than .3). When comparing genders in each group by type of schooling, significant gender differences were found in the schooled children. Girls scored significantly higher than boys on Emotional Regulation (U=881, z=2.15, p=.03, r=.25) and Attentional Problems (U=935.5, z=2.73, p=.01, r=.32) scales, and significantly lower on Willingness to Study (U=464.5, z=-2.37, p=.02, r=-.27). No significant gender differences were found among homeschooled children.

Table 4

Discussion

The objective of the present study was to compare the psychological adjustment of the homeschooled children and those schooled in educational centres. To do so, multi-informant measures (self and hetero-reports) were used. Our results showed that, in the self-reports, the homeschooled children scored significantly lower in Depression and Somatic Complaints. No differences were found in any of the other measures of socioemotional well-being. In the same vein, the parents’ view through the hetero-reports also showed that the homeschooled children scored significantly lower in Depression, Attentional Problems, and Willingness to Study than schooled children.

As we have seen, the gender differences were found only for the group of school children, both for the self-report scales ─Depression, Family Problems and Somatic Complaints─ and for the hetero-report scales ─Depression, Emotional Regulation and Attention Problems. On all these scales, school girls obtained higher scores than school boys.

One of the main results of this study was the consistency between parents’ and the children’s scores for the measure of depression. For school children, both also indicated higher scores for girls than for boys. It is especially striking that the differences were found in both the self-report and hetero-report measures. These results are congruent with those of other authors, such as Guterman and Neuman (2017a), who found that homeschooled children between the ages of 9 and 12 have significantly lower levels of depression. This result also coincides with extensive previous literature that consistently shows that the levels of depression are higher in girls (Albert, 2015; Balanza et al., 2009; Candila Fernández et al., 2015; Vázquez & Blanco, 2008; see Sanmartín et al., 2022 for recent prevalence data across Spanish adolescents). In our case, it is especially relevant that only the girls in the school group have these higher scores. We will further delve into the question of gender differences later.

Another interesting result has to do with the Somatic Complaint scores. Although this dimension was only evaluated by self-report, it is interesting to note that again there are differences between the two groups and that gender is relevant only in the group of school children, with girls scoring the highest. The Somatic Complaint Scale asks children to rate the frequency of certain physical complaints that are considered indicative of psychological manifestations. As some previous studies have shown, stomach aches, headaches, backaches, or fatigue in preschool children have been found to be predictive of depression and anxiety in childhood and adolescence (Lien et al., 2011; Shelby et al., 2013; Woods, 2020). On the other hand, children’s assessment of this symptomatology could be especially revealing, as it is a physical experience that can be much easier for children to assess than other issues more linked to emotions or thoughts. In this sense, it is feasible that the differences between the two groups and those based on gender in somatic complaints, where a medium effect size was found, support and add coherence to those found in the Depression scale.

Another scale in which differences are found is the so-called Willingness to Study. In this case, school children obtain higher scores than homeschooled children. This result might seem surprising, but analysing the items that compose this scale in a little more detail, it could be related to the content that it evaluates. In general, this scale refers to issues that can be important in the school context but not necessarily in the context of study of homeschooled children. Thus, some of these items are “Keep your tasks and homework up to date”, “Review what you have studied” or “He/She makes an effort in his/her studies”. It is possible that the homeschooled children way of learning does not need these types of activities or that the parents of homeschooled children consider that these types of activities are not relevant in their way of approaching learning. In this sense, a more informative and relevant measure to compare both groups could be motivation towards learning. In addition, as some previous studies point out, it is crucial to know which teaching methods homeschooling parents employ (Valiente et al., 2022; Wyatt, 2008). In our case, given the characteristics of the sample to which we had access, we do not have any information regarding the methodology followed by the parents of these children.

Finally, another interesting result of the present study is that related to gender differences. As we have already mentioned, these differences appear only in the group of school children and reveal a worse psychological adjustment in girls, both in the self-report (Depression, Somatic complaints, and Family problems) and the hetero-report (Depression, Emotional regulation, and Attentional problems). This result makes us reflect on the higher prevalence of certain psychological problems in girls (i.e., depression) and the role that school can play in it. Thus, on the one hand, as Ruiz Repullo (2017) points out, school can play an important role in breaking or maintaining gender stereotypes and roles from a very early age. In fact, in a recent observational study with children in Early Childhood Education in the United States, King (2021) found that teachers express more negative emotional states to boys and tend to minimize their negative emotions. On the contrary, in the treatment of girls there are no differences in the expression of positive and negative states nor are there negative emotional downplay. In this sense, some authors point out that our educational system is gender biased, as it does not educate girls and boys in the same way, and they recommend the elimination of practices such as the invisibility of female models in textbooks, the segregation by gender or even the formation of groups based solely on the criteria of gender (Subirats, 2016). This maintenance of gender stereotypes and roles could contribute to a greater incidence of depressive symptoms in school girls. In the case of homeschooled girls, it is possible that the educational practices of these families do not incur in gender stereotypes as much. Although this result may not be reliable due to the size of the sample, it would be interesting to investigate whether the educational practices of these families do not include gender stereotypes and whether this has any impact on the socioemotional well-being of the girls.

Taken together, our results suggest that homeschooled children present similar indices of socioemotional well-being compared to school children, and that they score higher on some scales. It is important to point out that the measures of social adjustment, one of the main concerns of the studies that have evaluated the well-being of homeschooled children, do not reveal social interaction difficulties in homeschooled children. Moreover, no differences were found in family interactions (neither in the Family Problems scale nor in the Challenging Behaviour scale) compared to school children. This result could contribute towards modifying the image that, at least in Spain, is usually held of families that educate their children at home. These families, which, in our country, are even in an illegal situation, tend to be perceived as peculiar families, even marginal, far from the usual patterns of social interaction and from any context with a certain influence in society. Our results, in line with the few previous works carried out without prior interest or expectations (Guterman & Neuman, 2017a, 2017b), suggest the need for more studies to better understand the impact that this type of schooling has on children’s development.

Lastly, this study is not exempt from limitations that restrict the scope of the results. Among the main limitations, it is necessary to point out the size of the sample and the lack of certain relevant information for the correct interpretation of the results. In this sense, the fact of working with a hidden sample makes it difficult to access the participants in a more direct way and to collect other types of relevant information, such as the educational level of the families, the reasons that led to the decision of homeschooling (religious issues, disagreement with the educational system, negative experiences in educational institutions, etc.), the methodology of teaching used in the family context or the time they have been homeschooling. All this variability can significantly impact the educational experience of students and, therefore, alter the results and their interpretation. In future studies, it would be necessary to have all this type of information. Another limitation has to do with the type of measures used, as we have only used questionnaires. This is a limitation shared with practically all the studies that analyse the socialization of homeschooled children, as Kuzman and Gaither (2020) point out, and that should be overcome in future works. Finally, our work is a cross-sectional study, and it would be interesting to know the long-term impact through longitudinal studies. Also, most of the studies have focused on Primary Education students (up to 12 years of age) and it would be interesting to focus efforts on determining whether, in the period of adolescence, due to the characteristics of this vital stage in which the family context loses weight compared to the importance of the group of friends, the results would be in the same vein. In the same sense, there is no research on the impact that home school has on access to university or working life in Spain.

Despite these limitations, it is necessary to highlight that the main strength of our study lies in having managed to access a sample of homeschoolers in Spain. As previously indicated, the non-regularized situation of home school in Spain makes it difficult to access this type of participants for research and, therefore, the study of the impact of this educational modality on the psychological adjustment of students. Prior studies have been carried out in contexts in which home school is legalized and, to our knowledge, this is the first study in which non-legalized home school families have been evaluated. This study can contribute to open the space for research on the impact of home school on child development. In addition, knowing the characteristics of this population and the scope of this type of educational practice would serve to establish good educational policies that ensure equal opportunities both for home school and school students.

Funding & Acknowledgments

This work has been funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (RTI2018-098631-B-I00). We are grateful to the principals, the teachers, the children, and the families that have participated.

References

Albert, P. R. (2015). Why is depression more prevalent in women? Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience, 40(4), 219-220.

Arai, A. B. (2000). Reasons for home schooling in Canada. Canadian Journal of Education, 25, 204-217.

Balanza, S., Morales, I., y Guerrero, J. (2009). Prevalencia de ansiedad y depresión en una población de estudiantes universitarios: factores académicos y sociofamiliares asociados. Clínica y Salud, 20(2), 177-187.

Blok, H., Merry, M. S., & Karsten, S. (2017). The legal situation of home education in Europe. In M. Gaither, (Ed.), The Wiley handbook of home education, (pp. 394-421). Wiley Blackwell.

Cabo, C. (2012). El homeschooling en España: Descripción y análisis del fenómeno. Tesis Doctoral. Universidad de Oviedo.

Dalaimo, D. M. (1996). Community home education: A case study of a public school-based home schooling program. Educational Research Quarterly, 19, 3-22.

Denham, S. A. (2023). The development of emotional competence in young children. Guilford Publications.

Farris, M. & Woodruff, S. (2000). The future of home schooling. Peabody Journal of Education, 75, 233-255.

Goiria, M. (22 de noviembre de 2022). El fenómeno del homeschooling o educación en casa. La opción de educar en casa. https://madalen.files.wordpress.com/2009/12/estudio-de-encuestas1.pdf

Guterman, O. & Neuman, A. (2017a). Schools and emotional and behavioral problems: A comparison of school-going and homeschooled children. The Journal of Educational Research, 110, 425-432.

Guterman, O. & Neuman, A. (2017b). What makes a social encounter meaningful:

The impact of social encounters of homeschooled children on emotional and

behavioral problems. Education and Urban Society, 48, 778-792.

Haugen, D. L. (2004). The social competence of homeschooled and conventionally-schooled adolescents. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, George Fox University, Newberg, OR.

King, E. K. (2021). Fostering toddlers’ social emotional competence: considerations of teachers’ emotion language by child gender. Early Child Development and Care, 191(16), 2494-2507. 10.1080/03004430.2020.1718670

Kunzman, R. & Gaither, R. (2020). Homeschooling: An updated comprehensive survey of the research. Other education: The Journal of Educational Alternatives, 9, 253-336.

Lien, L., Green, K., Thoresen, M., & Bjertness, E. (2011). Pain complaints as risk factor for mental distress: A three-year follow-up study. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 20, 509-516.

McQuiggan, M., Megra, M., & Grady, S. (2017). Parent and family involvement in education: Results from the National Household Education Surveys Program of 2016 (NCES 2017-102). U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, http://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2017102.

Medlin, R. G. (2000). Home schooling and the question of socialization. Peabody Journal of Education, 75, 107-123.

Meighan, R. (1995). Home-based education effectiveness: Research and some of its implications. Educational Review, 47, 275-287.

Murphy, (2014). The social and educational outcomes of homeschooling. Sociological Spectrum, 34, 244-272.

Neuman, A. (2019). Criticism and education: Dissatisfaction of parents who homeschool and those who send their children to school with the education system. Educational Studies, 45, 726-741.

Pennings, R., Sikkink, D., Van Pelt, D., Van Brummelen, H., & von Heyking, A.

(2012). A rising tide lifts all boats: Measuring non-government school effects in service of the Canadian public good. Cardus.

Romanowsky, M. (2001). Common arguments about the strenghts and limitations of home schooling. The Clearing House, 75, 79-83.

Ray, B. (2017). A review of research on homeschooling and what might educators

learn? Pro-Posições, 28, 85-103.

Ray, B. D. (2022). Research facts on homeschooling. National Home Education Research Institute. https://www.nheri.org/research-facts-on-homeschooling/

Ruiz Repullo, C. (2017). Estrategias para educar en y para la igualdad: coeducar en los centros. Revista Internacional de Estudios Feministas, 2(1), 166-191. http://dx.doi.org/10.17979/arief.2017.2.1.2063

Sanmartín, A., Ballesteros, J. C., Calderón, D. & Kuric, S. (2022). Barómetro Juvenil 2021. Salud y bienestar: Informe Sintético de Resultados. Centro Reina Sofía sobre Adolescencia y Juventud, Fundación FAD Juventud.

Shelby, G.D., Shirkey, K.C., Sherman, A.L., Beck, J.E., Haman, K., Shears, A.R., et al. (2013). Functional abdominal pain in childhood and long-term vulnerability to anxiety disorders. Pediatrics, 132, 475-82.

Shyers, L. (1992). A comparison of social adjustment between home and traditionally schooled students. Home School Researcher, 8, 1-8.

Subirats, M. (2017). Coeducación, una apuesta por la libertad. Octaedro.

Sutton, J. P. & Galloway, R. S. (2000). College success of students from three

high school settings. Journal of Research and Development in Education, 33, 137- 146.

Taylor, J. (1986). Self-concept in home-schooling children. Home School Researcher, 2, 1-3.

Valiente, C., Spinrad, T. L., Ray, B. D. Eisenberg, N., & Ruof, A. (2022). Homeschooling: What do we know and what do we need to learn? Child Development Perspectives, 16, 48-53.

Vázquez, F.L., y Blanco, V. (2008). Prevalence of DSM-IV Major Depression Among Spanish University Students. Journal of American College Health, 57(2), 165-171.

Woods, S.B. (2020). Somatization and disease exacerbation in childhood. En K.S. Wampler & L.M. McWey (Eds.), The handbook of systemic family therapy (pp. 321-341). John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Wyatt, G. (2008). Family ties: Relationships, socialization, and home schooling. University Press of America. ¯